The skies above the Amazon have changed. Where once vibrant shades of green carpeted the land, where life hummed in the harmony of nature’s ancient rhythm, there is now a deep wound, spreading across the Earth’s lungs. The pulse of the planet falters, its breath clouded by smoke and flames. This is not a future science fiction tale, but the grim reality of the present—a chapter we thought we could avoid, yet here we are.

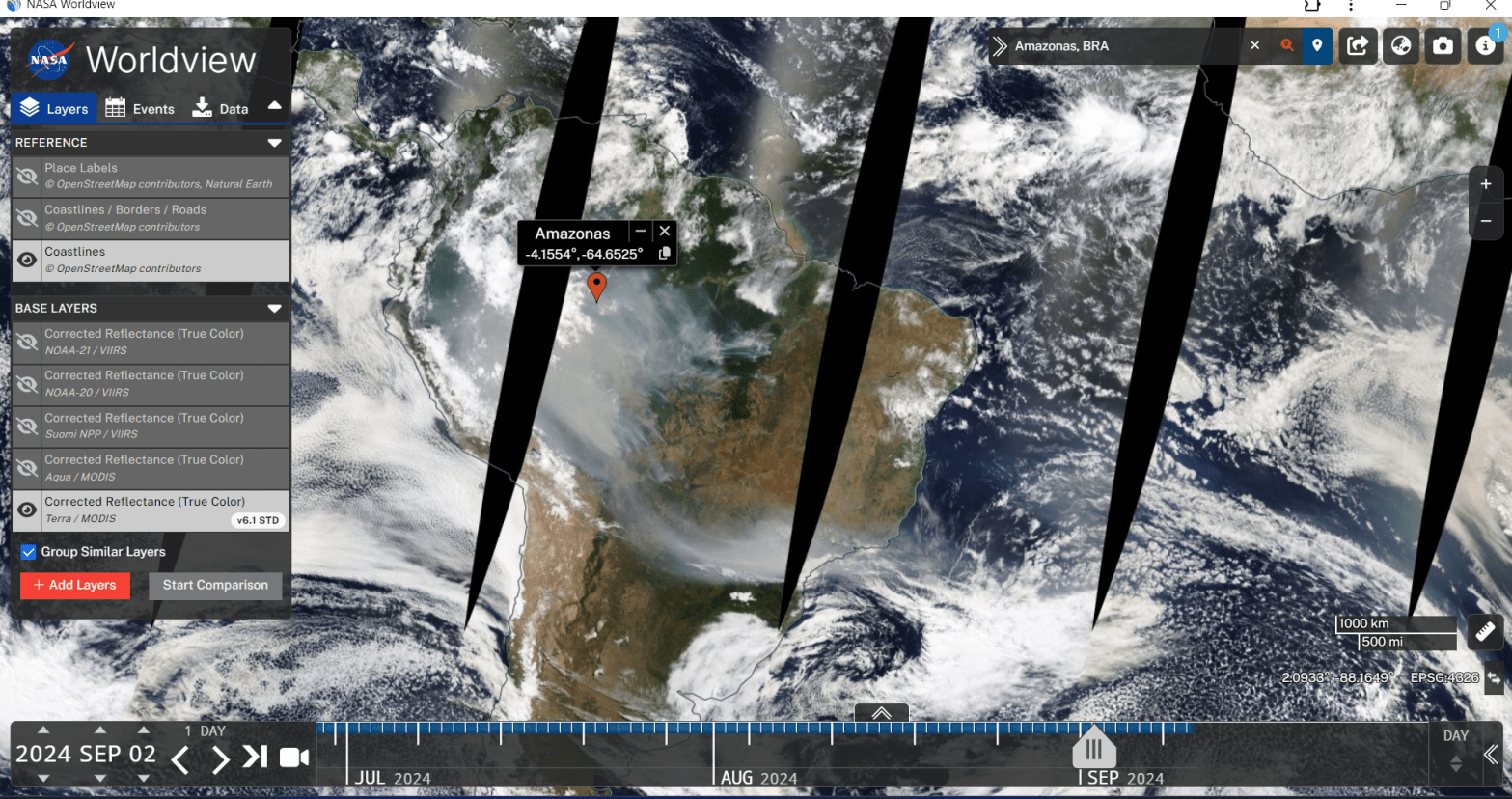

It is September 2024, and the satellite images from space no longer show the thriving expanse of green we had once taken for granted. Instead, the once lush forest is hidden beneath a veil of smoke, like a dying ember smoldering in the ashes of what was once a living, breathing ecosystem. Fires rage across the Amazon, sending plumes of smoke high into the atmosphere. The world watches, but few truly see. The layers of the Earth’s fragile atmosphere reflect the chaos below, while the devastation unfolds slowly, relentlessly.

The Amazon—a sanctuary for over 10% of the Earth’s known biodiversity—has become a battlefield, but this war is not fought with guns. Instead, it is a slow suffocation, a strangulation of the natural cycles that have sustained life for millennia. The very lifeblood of the planet is bleeding out, a death by a thousand cuts, each incision more fatal than the last.

The Fall of a Giant: Satellite Evidence of a Dying Forest

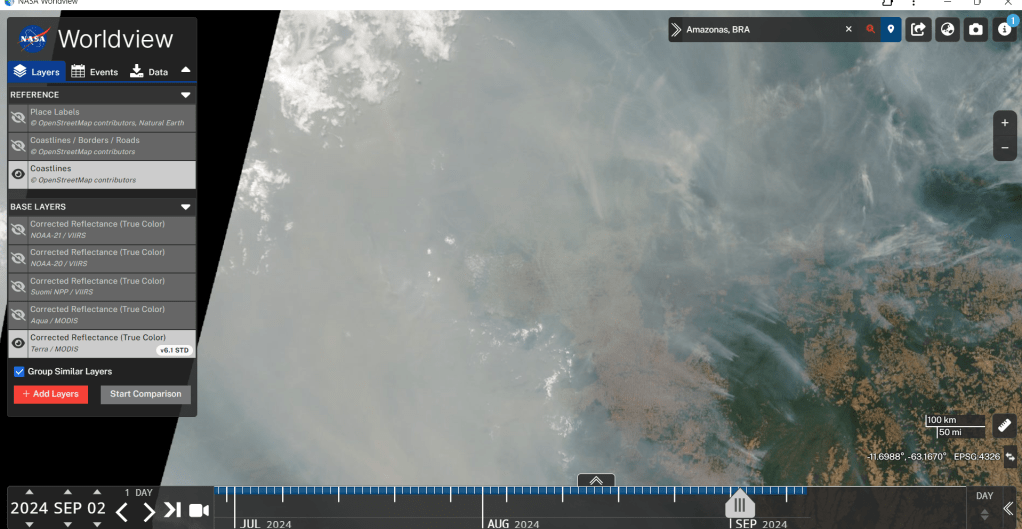

The satellite image from NASA, taken on the second of September 24, marks yet another milestone in the Amazon’s collapse. Dark plumes of smoke stretch across the region of Amazonas, suffocating not only the trees but every form of life that depends on the forest’s delicate balance. The fires are not natural; they are the byproduct of human greed, fueled by decades of deforestation, slash-and-burn agriculture, and a warming climate that turns once-wet seasons into dry tinderboxes. This is no longer a localized disaster—it is the crumbling of an entire ecosystem that affects the stability of our climate system globally.

The Amazon, once a carbon sink, is now hemorrhaging carbon into the atmosphere. Its vast expanse of trees, which used to absorb the Earth’s excesses, is now burning and releasing years of stored carbon. The cycle is spiraling downward—a dystopian loop that we cannot seem to break. But unlike in fiction, there is no escape to another planet, no grand hero to save the day. This is our reality, and the consequences will be far-reaching.

The Thick Smoke of a Suffocating Forest

As the satellite images roll in from early September 2024, the extent of the damage becomes ever clearer. A thick haze of smoke, dark and oppressive, blankets the Amazon rainforest. It twists and churns through the atmosphere, veiling the land below in a cloak of destruction. But this is no ordinary fog—this is the smoke of death, the unmistakable signature of fires set ablaze, sparked by the hand of man and the parched earth below.

The fires were not sudden; they crept upon the forest, ignited by droughts that have grown more intense each year. The relentless dry seasons, stretching longer and more unforgiving, have made the land a tinderbox waiting to ignite. And now it burns, with fires feeding off the very lungs of the planet. The drought, a cruel messenger of climate change, has left the land brittle and dry, making what was once the world’s largest rainforest vulnerable to the flames.

Beneath the smoke, there is devastation. As the thick layers of smoke begin to disperse—carried by winds—the satellite imagery gives us a glimpse into the horror below. Where there was once a thriving canopy, teeming with life and unimaginable biodiversity, there is now nothing but barren, cleared land. The dark patches are the charred remains of trees that once stood tall and proud. What is left is nothing but a vast emptiness, an open scar on the Earth’s surface where the Amazon once flourished.

These are not accidental fires, not wildfires of nature’s making. These are fires deliberately set, to clear land for agriculture, for cattle ranching, for palm oil, and for soy. The lifeblood of the planet is traded for short-term profit, leaving behind nothing but wasteland. Entire sections of the forest, thousands of square kilometers, are now gone, and beneath the suffocating veil of smoke, the forest’s once vibrant spirit lies in ruins.

But this isn’t just a tragedy for Brazil. As the trees burn, they release vast amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, accelerating the feedback loop of climate change. The Amazon, once a carbon sink, a crucial buffer against the rising temperatures of our planet, is now becoming part of the problem it was once relied on to solve. It is now a carbon emitter, contributing to the warming that is causing its own destruction.

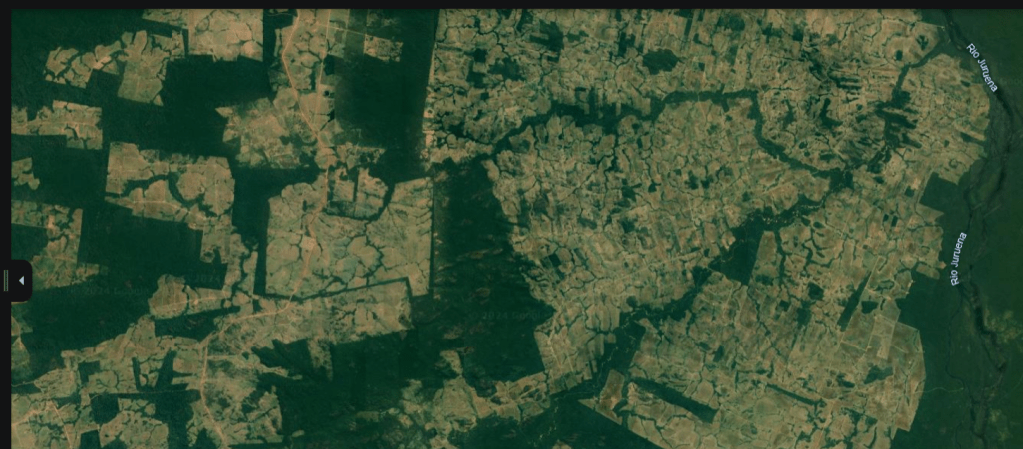

The area below is close to the size of Texas, and half of the area is devastated forest burned by droughts or people to get cleared forests.

We can look even closer how such a cleared tropical rain forest looks like.

The satellite image above shows the devastation with cold precision: swathes of cleared land, square and geometric, as though nature could be partitioned and tamed. But there is no taming the Amazon. It is a living organism, and like all living organisms, it cannot survive being carved into pieces. The dark green patches are the remnants of what was once an endless expanse of rainforest—now reduced to islands of life, disconnected and vulnerable.

This is the heart of the deforestation crisis. The patchy clearings that seem to spread like a virus, each new section cut down to make way for grazing land or plantations. The intricate web of life that once existed in these areas has been severed. Where there were once thick canopies, teeming with insects, birds, and mammals, there are now only open fields and the silent stumps of trees. Rivers like the Rio Juruena, seen snaking through the image, are now surrounded by barren lands instead of the protective forest they once flowed through.

The fragmentation of the forest is devastating for biodiversity. Animals that rely on large territories, such as jaguars or harpy eagles, find themselves trapped in shrinking patches of forest, their hunting grounds and nesting areas disrupted. The once-dense forest has been reduced to isolated fragments, preventing the natural flow of life and migration. Species that have lived in this region for millennia are suddenly without a home.

Tarzan, where are you?

Let’s go closer to the ground:

As we zoom closer, the scale of destruction becomes overwhelming. The small, geometric clearings stretch in every direction, like a disease spreading across the land. Each square represents not only lost trees but also lost potential for the planet. The Amazon, often referred to as the “lungs of the Earth,” is no longer breathing. The forests that once absorbed billions of tons of carbon dioxide now lie in ruin, unable to offer the planet any reprieve from the onslaught of climate change.

The land is sick, its soil eroded and dry, its trees fallen and burned. What we see here is a dystopia in real time—a landscape ravaged by the pursuit of profit, where the consequences will ripple outward far beyond the borders of the Amazon. It is not just the creatures of the forest that are losing their home. Humanity, too, will suffer as the forest continues to disappear. The rain that once nourished this region will lessen, the carbon stored in these trees will be released, and the balance we took for granted will tip further into chaos.

The ground, once rich with life, now carries the weight of its absence. The Amazon’s future—and by extension, our future—looks bleak unless we heed this warning and act to stop this silent apocalypse from spreading further.

But I don’t want to stop here. There are still solutions, but we need to do them collectively, and that’s the actual problem. Technically, we still can solve at least mitigate the problem effectively.

The non-profit organization SwitchCoal.org (https://www.switchcoal.org/) founded by economists, engineers and computer scientists found out in a profound analyses about Transitioning Coal Plants to Renewable Energy that the conditions in locations of current big coal exploitation areas are almost ideal from technical and economical standpoint.

The study outlines a comprehensive strategy to transition the world’s approximately 2500 coal-fired power plant sites to renewable energy, primarily wind-solar-battery systems.

1. Economic Viability of Switching from Coal to Renewables

- The study emphasizes that switching coal plants to wind-solar-battery systems can be profitable for 90% of global coal plants. This profitability comes from lower operating costs and leveraging existing grid connections at coal sites, shortening planning and connection times.

- Investments in renewable energy, backed by reports from Bloomberg NEF, IRENA, and the International Energy Agency (IEA), show that it is already cheaper to operate wind and solar farms compared to many coal plants. This financial incentive is particularly strong, with billions in additional profits projected over the 30-year service life of these renewable systems.

2. Potential Environmental Impact

- Switching could reduce up to 10 Gigatons of CO2 emissions annually before 2030, contributing substantially to global climate goals, particularly the 1.5°C limit set in the Paris Agreement.

- Renewable installations at coal plant sites would reduce emissions by repurposing grid connections and energy infrastructure, minimizing logistical delays.

3. Employment Benefits

- The transition would offer retraining opportunities for existing coal plant workers. With the installation of solar and wind systems, these workers could be retained and employed in assembling and installing these systems, easing the socio-economic transition.

4. Country-by-Country Results

- The document provides a detailed breakdown by country, indicating how many coal plants can be profitably switched, the investment needed, and the potential profits. For example, Australia, China, and Germany stand out as having significant potential for profitably replacing coal with renewable systems.

5. Wind and Solar Potential

- The study assesses both wind and solar potentials at the coal plant sites. About 74% of the sites have sufficient solar potential to produce electricity at 4 US cents per kWh or less, and 68% of the sites have wind speeds sufficient to generate energy at the same cost. This data indicates a strong technical foundation for switching to renewables at these locations.

6. System Optimization

- The study explores two optimization models for balancing wind and solar energy. A physics-based model aims for stable energy production throughout the year, while an economic model focuses on the cheapest possible energy mix. Both approaches confirm the profitability and feasibility of the transition.

7. Global Feasibility by 2030

- The study argues that current global manufacturing capacities for wind and solar are sufficient to transition coal plants to renewable energy by 2030. This conclusion is bolstered by growing annual production capacities, particularly in solar photovoltaics.

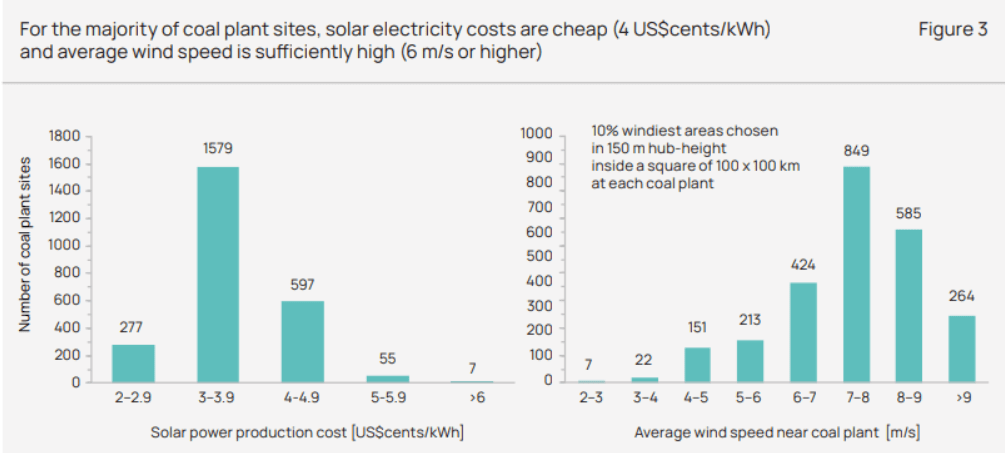

The attached image presents two key pieces of data related to the solar and wind potential at coal plant sites, highlighting why the majority of these sites could transition to renewable energy with competitive costs:

Left Graph: Solar Power Production Costs

- This graph shows the distribution of solar power production costs (in US cents per kilowatt-hour, kWh) across coal plant sites.

- Most coal plant sites (about 1,579 of them) are located in regions where solar energy can be produced at a cost between 3 and 3.9 US cents per kWh, which is considered cheap.

- A significant number (277 sites) can produce solar energy even more cheaply, at costs between 2 and 2.9 US cents per kWh.

- The trend indicates that 74% of the sites (adding up to the categories below 4 US cents per kWh) have access to solar potential where production costs are below 4 US cents/kWh—a critical price point to ensure the profitability of solar installations.

- Only a small percentage (55 sites) would need to produce solar energy at costs above 5 US cents/kWh, showing that most coal plant sites are in regions favorable to solar energy.

Right Graph: Average Wind Speed Near Coal Plant Sites

- This graph shows the average wind speed at coal plant sites in meters per second (m/s), which is important for assessing the potential of wind energy.

- Most of the sites (849) have average wind speeds of 6-7 m/s, which is sufficient for cost-effective wind energy production.

- Another significant portion (585 sites) have wind speeds of 7-8 m/s, which enhances the economic viability of wind energy, as higher wind speeds typically lead to lower energy production costs.

- Sites with wind speeds above 9 m/s (264 sites) are optimal for generating the most cost-efficient wind energy.

- Wind speeds between 6-9 m/s are considered ideal for competitive wind energy production, which covers 68% of the coal plant sites.

This supports the argument in the SwitchCoal study that most of the world’s coal plants are located in areas where both solar and wind energy can be produced at competitive rates. Specifically:

- 74% of the coal sites can transition to solar energy at costs below 4 US cents/kWh.

- 68% of the coal sites are in regions with sufficient wind speeds (6 m/s or higher) to generate wind energy at similarly low costs.

This data suggests that these sites are prime candidates for transitioning from coal to renewable energy sources, helping to both reduce greenhouse gas emissions and cut operational costs.

There are feasible solutions to combat Climate Change, but are we going to implement them?

very useful Post.

LikeLiked by 1 person