Scotty,…Energie!

Systembilanz 2025: Warum unser Stromnetz nicht kollabiert ist (und sogar grüner wurde)

Wer die Energiewende nur aus Schlagzeilen kennt, könnte meinen, das deutsche Stromnetz sei ein fragiles Gebilde, das bei jeder Wolke am Himmel zittert. Als (Software-/Elektro-)Ingenieur schaut man lieber auf die nackten Betriebswerte. Und die Bilanz für 2025 zeigt: Das „System Deutschland“ ist effizienter und regenerativer als je zuvor.

Werfen wir einen Blick in das Maschinenraum-Protokoll des letzten Jahres.

Die Erzeugungsmatrix: Wer liefert die Grundlast?

Im Jahr 2025 haben wir insgesamt 440 Terawattstunden (TWh) netto ins öffentliche Netz eingespeist. Wenn wir das als Gesamtsystem betrachten, sehen wir eine massive Verschiebung der Prioritäten. Die „Erneuerbaren“ sind nicht mehr nur ein nettes Add-on, sie sind das Betriebssystem.

| Komponente | Output (TWh) | Anteil am Mix | Engineering-Status |

| Wind (On- & Offshore) | 131,9 | 30,0 % | Der Heavy-Lifter im System. |

| Fotovoltaik | 70,6 | 16,0 % | Massive Peak-Leistung im Sommer. |

| Biomasse & Wasser | 53,8 | 12,2 % | Die „regelbare“ grüne Reserve. |

| Braunkohle | 67,2 | 15,3 % | Nur noch im Einsatz, wenn die Residuallast drückt. |

| Erdgas | 56,5 | 12,8 % | Die schnelle Eingreiftruppe für Lastspitzen. |

Das „Import-Paradoxon“: Kaufen wir nur Atomstrom?

Ein oft gehörtes Argument lautet: „Wir schalten ab und kaufen den Atomstrom von den Nachbarn.“ Schauen wir uns die Lastfluss-Analyse an.

Deutschland war 2025 Netto-Importeur (ca. 22 TWh Saldo). Aber wir importieren nicht, weil wir „zu wenig“ Strom haben, sondern weil der europäische Strommarkt nach dem Merit-Order-Prinzip funktioniert. Wenn in Dänemark der Wind weht oder in Norwegen die Stauseen voll sind, ist dieser Strom billiger als unsere eigenen Kohlekraftwerke. Wir importieren also aus wirtschaftlicher Logik, nicht aus technischer Not.

Die reale Kernenergie-Quote

Wenn wir die gesamte Last (den Verbrauch inklusive Importe) berechnen, ergibt sich für die Kernenergie ein Anteil von gerade einmal ~1,2 %.

Technischer Vergleich: Das ist so, als würde man ein Hochleistungssystem mit 100 Modulen betreiben und eines davon wäre noch ein altes Legacy-Bauteil aus dem Ausland. Systemrelevant? Kaum. Messbar? Ja.

Netzstabilität und Residuallast: Die wahre Herausforderung

Die eigentliche Ingenieursleistung 2025 war nicht die Erzeugung an sich, sondern das Einspeisemanagement. Wir haben einen Anteil von fast 60 % fluktuierender Energie im Netz stabil gehalten. Das erreichen wir durch:

- Intelligente Laststeuerung: Industrie und Heimspeicher fangen Spitzen ab.

- Europäischer Verbund: Wir nutzen das Netz der Nachbarn als Puffer (Interkonnektoren).

- Gaskraftwerke als Backup: Dank ihrer schnellen Hochlaufkurven sind sie die idealen Partner für Wind und Solar.

Zwischen Fazit

Die Bilanz 2025 zeigt: Die Dekarbonisierung des Stromsektors ist kein Experiment mehr, sondern ein stabiler Dauerbetrieb. Kohle wird durch Grenzkosten und CO₂-Zertifikate aus dem Markt gedrängt, während Wind und Solar die Grenzkosten gegen Null drücken.

Wir haben 2025 bewiesen, dass ein Industrieland mit minimalem Nuklear-Anteil (1,2 % via Import) und sinkender Kohleverstromung sicher funktionieren kann. Das System läuft stabil – und es läuft sauberer.

Detaillierung der Strommix-Bilanz 2025.

Es ist wichtig, zwischen der reinen Inlandsproduktion und dem Verbrauchsmix (Last) zu unterscheiden. Wenn wir die Netto-Importe einbeziehen – also den Strom, der tatsächlich durch die deutschen Haushalte und das Gewerbe fließt –, knacken wir bei den Erneuerbaren wahrlich die 60-Prozent-Marke.

Der deutsche Stromverbrauchsmix 2025 (Lastbilanz inkl. Importe)

Diese Tabelle zeigt die Zusammensetzung des öffentlichen Stromverbrauchs. Sie berücksichtigt sowohl die inländische Einspeisung ins öffentliche Netz als auch den Saldo aus Importen und Exporten.

| Energiequelle | Anteil (relativ in %) | Status im System |

| Erneuerbare Energien (Gesamt) | 61,7 % | Dominanter Systempfeiler |

| – davon Windkraft | 30,8 % | Volatile Grundlast |

| – davon Fotovoltaik | 16,4 % | Peak-Abdeckung |

| – davon Biomasse / Wasser / Sonstige | 12,1 % | Regelbare grüne Energie |

| – davon RE-Anteil aus Importen | 2,4 % | Grüne Zukäufe (DK/NO/AT) |

| Braunkohle | 15,3 % | Träge Residuallast |

| Erdgas | 13,0 % | Hochflexible Lastfolge |

| Steinkohle | 6,1 % | Rückläufige Reserve |

| Kernenergie (nur Import) | 1,2 % | Physischer Grenzfluss |

| Sonstige (Müll/Öl/fossile Importe) | 2,7 % | System-Rauschen / Industrie |

Warum die 60-Prozent-Hürde so bedeutend ist

Aus technischer Sicht ist dieser Wert ein Meilenstein. Dass wir heute bei über 60 % Erneuerbaren im öffentlichen Mix liegen, pulverisiert die alten Prognosen aus der Zeit um die Jahrtausendwende. Damals hieß es in konservativen und industrienahen Papieren oft, das Netz würde bei mehr als 4 % fluktuierender Einspeisung instabil werden, da die „Massenträgheit“ der großen rotierenden Generatoren fehle.

Hintergrund:

- Netzdynamik: Wir haben die fehlende mechanische Trägheit durch ultraschnelle Leistungselektronik (Wechselrichter) und intelligentes Engpassmanagement (Redispatch) ersetzt.

- Import-Qualität: Die Tatsache, dass der Erneuerbare-Anteil durch Importe sogar stabil bleibt oder steigt, liegt an der hohen Qualität der Importe (viel Wind aus Dänemark und Wasserkraft aus Norwegen).

- Nuklear-Anteil: Der Kernenergie-Anteil mit 1,2 % im Gesamtmix ist marginal. Er resultiert primär aus den physikalischen Lastflüssen im europäischen Verbundsystem und spielt für die Gesamtstabilität des deutschen Netzes keine steuernde Rolle mehr.

Der Zappelstrom „debunked“

Um die heutige Stabilität des Netzes bei über 60 % erneuerbarem Anteil zu würdigen, muss man einen Blick zurückwerfen. Am 26. Juni 1993 schaltete eine Gruppe großer deutscher Stromversorger (darunter RWE und PreussenElektra) eine mittlerweile legendär gewordene Anzeige in großen Tageszeitungen wie der Süddeutschen Zeitung.

Darin hieß es wörtlich:

„Regenerative Energien wie Sonne, Wasser oder Wind können auch langfristig nicht mehr als 4 % unseres Strombedarfs decken.“

Die Argumentation war damals sowohl politisch als auch schein-technisch untermauert: Konservative Kreise und Industrievertreter warnten massiv davor, dass ein höherer Anteil an „Zappelstrom“ die Netzfrequenz von 50Hz unkontrollierbar machen würde. Man behauptete, die fehlende Trägheit der riesigen Turbinenmassen in Kohle- und Kernkraftwerken würde bei Wolkenzug oder Windstille unweigerlich zum Netzzusammenbruch führen.

Heute wissen wir: Das war kein physikalisches Naturgesetz, sondern ein Mangel an (gewollter) technischer Innovation. Die Ingenieursleistung der letzten Jahrzehnte hat bewiesen, dass intelligente Wechselrichter und digitales Lastmanagement die Netzfrequenz präziser steuern können als die alten mechanischen Systeme.

Die Kosten der Freiheit: Warum die Stromrechnung trotzdem steigt

Wenn Wind und Sonne „keine Rechnung schicken“, warum ist der Strom in Deutschland dann so teuer? Als Ingenieure müssen wir uns die Kostenstruktur genau ansehen. Wir erleben gerade einen Systemwechsel: weg von hohen Brennstoffkosten (Kohle/Gas), hin zu hohen Systemkosten (Netz).

1. Das Netzentgelt-Dilemma

Der größte Preistreiber sind aktuell die Netzentgelte. Während die Erzeugungskosten für Fotovoltaik und Windkraft (LCOE – Levelized Cost of Electricity) massiv gesunken sind, steigen die Kosten für den Transport:

- Netzausbau: Um den Strom von den Windparks im Norden zu den Industriezentren im Süden zu bringen (Stichwort: SuedLink), müssen Milliarden investiert werden.

- Redispatch: Da das Netz oft an seine Grenzen stößt, müssen Kraftwerke kurzfristig hoch- oder heruntergefahren werden, um Engpässe auszugleichen. Das kostete 2025 erneut Milliardenbeträge, die auf den Strompreis umgelegt werden.

2. Transformation als Investition (Capex vs. Opex)

Man muss es nüchtern betrachten: Wir bauen gerade das gesamte „Betriebssystem“ der deutschen Industrie um.

- Früher (Opex-lastig): Wir hatten niedrige Baukosten für Kraftwerke, aber hohe laufende Kosten für Brennstoffe und CO₂-Zertifikate.

- Heute (Capex-lastig): Wir haben hohe Investitionskosten für Infrastruktur, Speicher und digitale Steuerung, aber dafür Brennstoffkosten von nahezu null.

Zwischenfazit: Eine Transformation kostet Geld. Aber während Investitionen in Kohle und Gas „verbranntes“ Geld sind, das in Abhängigkeiten fließt, sind Investitionen in das Netz und Speicher Investitionen in Innovation.

Innovation durch Schmerz: Der deutsche Exportartikel von morgen

Ja, die Strompreise für Endkunden und Mittelstand sind 2025 eine Herausforderung. Doch genau dieser Druck erzeugt eine Innovationswelle, die langfristig den Standort sichert:

- Smart Grids: Deutschland entwickelt gerade die weltweit fortschrittlichsten Steuerungsalgorithmen für dezentrale Netze.

- Speicher-Technologien: Vom Heimspeicher bis zu industriellen Wasserstoff-Lösungen entstehen hier Patente, die wir morgen weltweit exportieren.

- Effizienz: Hohe Preise zwingen die Industrie zu maximaler Energieeffizienz – ein Wettbewerbsvorteil, wenn Energie weltweit knapper wird.

Langfristiges Denken schlägt kurzfristigen Populismus

Erinnern wir uns an die RWE-Anzeige von 1993? Ich erinnere mich wohl daran, auch weil ich die Uni in diesem Jahr verließ und mir klar war, dass der Praxisschock nun nicht mehr zu vermeiden war. Wie beschrieben wurden mehr als 4 % Zappelstrom technisch als unmöglich angesehen. Heute wissen wir: Die Ingenieure haben das Problem gelöst. Dasselbe erleben wir heute bei den Kosten. Wer behauptet, wir könnten durch eine Rückkehr zu alten Strukturen (wie dem Neubau von Kernkraftwerken, die laut aktueller LCOE-Analysen die teuerste aller Energieformen sind) Geld sparen, ignoriert die ökonomische Realität.

Unerwartete Entwicklungen im Bereich Zappelstrom: Die Rolle der deutschen Justiz

Doch es hat sich auch in einem von mir sehr unerwarteten Bereich einiges pro Zappelstrom entwickelt – und das ist die deutsche Justiz. Besonders hervorzuheben ist das legendäre Klimaschutzurteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichts von 2021. Dieses Urteil hat deutlich gemacht, wie weitreichend die rechtlichen Rahmenbedingungen mittlerweile auf den Schutz des Klimas und die Transformation des Energiesystems ausgerichtet sind. Die Entscheidung des höchsten deutschen Gerichts hat nicht nur die politischen und wirtschaftlichen Akteure gezwungen, konsequent auf erneuerbare Energien und innovative Lösungen zu setzen, sondern auch einen wichtigen Impuls für die gesellschaftliche Akzeptanz und Umsetzung geliefert.

Und dabei ist es nicht geblieben. Letzte Woche erging das Urteil der Klimaklage der Deutschen Umwelthilfe (DUH) gegen die Bundesregierung. Worum ging es in dieser Klage? Die DUH fordert, dass die Bundesregierung ausreichende Maßnahmen gesetzlich implementiert, um die Klimaemissionen Deutschlands bis 2030 um 65 % gegenüber den Emissionen von 1990 zu reduzieren.

Barbara Metz und Jürgen Resch, die beiden Bundesgeschäftsführer der DUH, wurden von zwei Anwälten und einem Experten am Urteilstag begleitet. Die Bundesregierung besetzte mit ihren Vertretern den halben Sitzungssaal, was den Gerichtspräsidenten zu dem Kommentar veranlasste: „Hier sitzt ja das halbe Kanzleramt.“ Die Bundesregierung antwortete auf die Klage der DUH, indem sie die Klageberechtigung eines Umweltverbandes in Klimaangelegenheiten infrage stellte.

Kurz nach halb drei betraten die fünf Richter den Saal und verkündeten das Urteil:

Die DUH ist klageberechtigt und die Bundesregierung muss ein Klimaschutzprogramm umsetzen, mit dem das Minderungsziel von 2030 eingehalten wird. Mit diesem Urteil hat die DUH einen rechtlichen Titel, dieses Urteil auch gegenüber der Merz-Regierung vollstrecken zu können.

Meine persönliche Meinung ist, dass unsere geliebte Autoindustrie selbst das Umweltbewusstsein in der deutschen Justiz gestärkt hat. Seit Bekanntwerden des Diesel-Skandals wurde diese mit Klagen von betrogenen Autobesitzern des VW-Konzerns überschüttet und es dämmerte der Justiz, dass das deutsche und europäische Umweltrecht in manchen Konzernetagen nicht so richtig angekommen war. Newton hätte wohl gesagt: „Actio gleich Reactio“.

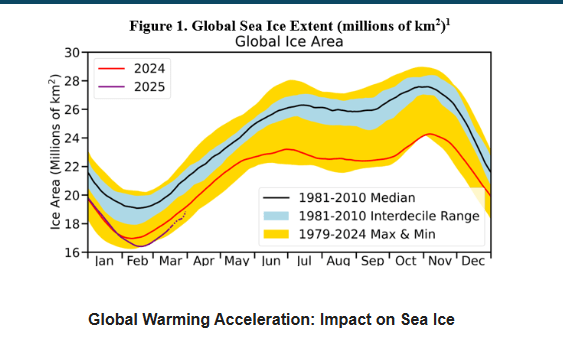

Warum 60 % erst der Anfang sind: James Hansen und der „faustsche Pakt“

Trotz des Meilensteins von 60 % Erneuerbaren im deutschen Netz mahnen führende Wissenschaftler, dass uns die Zeit davonläuft – und zwar schneller, als es die offiziellen Berichte des Weltklimarats (IPCC) vermuten lassen. Hier schwelt ein fachlicher Konflikt: Während der IPCC in seinen Modellen von einer linearen Erwärmung ausgeht, warnt das Team um den renommierten Klimaforscher James Hansen vor einer massiven Beschleunigung.

Hansen argumentiert, dass wir uns in einem „Faustschen Pakt“ mit der fossilen Industrie befinden. Das bedeutet präziser beschrieben: Die Verbrennung von Kohle und Öl hat nicht nur CO₂ freigesetzt (das den Planeten wärmt), sondern auch Schwefel-Aerosole. Diese Partikel wirken in der Atmosphäre wie ein kühlender Sonnenschirm, der einen Teil der Erwärmung maskiert hat.

Indem wir nun – richtigerweise – die Kohlekraftwerke abschalten und die Schifffahrt entschwefeln, lösen wir diesen Pakt auf. Der kühlende Schirm verschwindet schneller, als das CO₂ abgebaut werden kann. Die Folge? Die „verborgene“ Wärme bricht sich Bahn. Für uns bedeutet das: Die 60 % sind ein Etappensieg, aber keine Ziellinie. Wir müssen das System noch schneller dekarbonisieren, um die Rechnung für diesen jahrzehntelangen Pakt zu begleichen.

Und wenn ich das so sagen darf: Wie bei meinem literarischen Namensvetter zeigt sich auch beim Klima, dass man den Preis für den schnellen Fortschritt der Vergangenheit nicht ewig aufschieben kann. Die Physik fordert jedoch ihre Schulden ein – und wir alle, Erzieher im Kindergarten und Schulen, Handwerker, Seelsorger, Künstler, Ingenieure, Architekten, Mediziner, Politiker, Ökonomen und alle, die ich vergessen habe, müssen die Lösungen liefern, bevor die Zeit abläuft.

Der Riss in der Realität: Warum der Fall Renee Good Amerika nicht spaltet, sondern die Spaltung nur beweist

(Dieser Blog wurde mit Hilfe von Mistral.ai erzeugt)

Wir starren alle auf denselben Bildschirm. Wir sehen alle dasselbe Video aus Minneapolis: Ein Auto, Schnee, ein ICE-Beamter, Schüsse. Und doch sehen wir zwei völlig unterschiedliche Filme.

Für die eine Hälfte Amerikas ist das Video ein Snuff-Film, der Beweis für einen staatlich sanktionierten Mord an einer Mutter. Für die andere Hälfte ist es ein Lehrvideo über „Law & Order“, der Beweis für die notwendige Neutralisierung einer Bedrohung.

Wie ist das möglich? Wie können Millionen Menschen dieselben Photonen auf ihrer Netzhaut empfangen und im Gehirn zu zwei gegensätzlichen Realitäten verarbeiten?

Die Antwort liegt nicht nur in der Politik. Sie liegt in der Psychologie. Genauer gesagt: in der kognitiven Dissonanz.

Der Schmerz der Wahrheit

Die These ist simpel, aber erschreckend: Wir ertragen die Realität nicht mehr, wenn sie unser Identitätsgerüst bedroht.

Stellen Sie sich vor, Sie gehören zum „Roten Amerika“. Ihr Weltbild basiert auf Säulen wie: Die Polizei ist gut. Der Staat schützt uns vor dem Chaos. Wer nichts Falsches tut, hat nichts zu befürchten. Dann sehen Sie Renee Good. Eine unbewaffnete Frau, erschossen von „den Guten“. In diesem Moment schreit Ihr Gehirn auf. Es entsteht kognitive Dissonanz. Wenn dieser Schuss ungerechtfertigt war, dann ist Ihr Weltbild falsch. Dann sind die „Guten“ vielleicht böse. Das ist psychologischer Stress, der fast körperlich wehtut.

Um diesen Schmerz zu lindern, haben Sie nur zwei Möglichkeiten:

- Akkommodation: Sie ändern Ihr Weltbild („Vielleicht hat die Polizei ein Gewaltproblem“). Das ist schwer, schmerzhaft und isoliert Sie von Ihrer Gruppe.

- Assimilation: Sie biegen die Realität so hin, dass sie wieder in Ihr Weltbild passt.

Hier kommt Renee Good ins Spiel. Damit das Weltbild „Law & Order“ überlebt, muss Renee Good schuldig sein. Sie darf keine unschuldige Mutter sein. Also sucht das Gehirn verzweifelt nach einem Ausweg. Und hier liefern die Echokammern die Erlösung.

Die mediale Manifestation des Glaubens

Früher mussten wir diesen inneren Konflikt selbst lösen. Heute übernehmen das die Algorithmen für uns. Das ist der Moment, in dem die Spaltung vollzogen wird.

Wenn der konservative Familienvater in Kansas das Video sieht und den Schmerz der Dissonanz spürt, schaltet er Fox News ein oder öffnet X (ehemals Twitter). Dort wird ihm sofort das Schmerzmittel gereicht:

- „Sie hat das Auto als Waffe benutzt.“

- „Sie war eine linke Agitatorin.“

- „Schau dir ihre Vorstrafen an.“

Ah. Erleichterung. Das Weltbild wackelt nicht mehr. Sie war böse, ergo war der Schuss gerechtfertigt. Die kognitive Dissonanz ist aufgelöst, die Realität wurde erfolgreich umgedeutet.

Auf der „Blauen Seite“ passiert dasselbe, nur spiegelverkehrt. Das Weltbild hier: Das System ist rassistisch/faschistisch und will uns unterdrücken. Jedes Detail, das vielleicht Nuance in den Fall bringen könnte (z.B. wenn das Auto sich tatsächlich gefährlich bewegt hätte), würde Dissonanz erzeugen. Also filtern liberale Medien alles heraus, was nicht ins Bild der „perfekten Märtyrerin“ passt. Die Dichterin, die Mutter, die Unschuldige.

Wenn zwei Linien sich nie mehr treffen

Das Ergebnis dieser psychologischen Schutzmechanismen ist das, was wir heute in Minneapolis sehen: Der Tod der gemeinsam durchlebten Realität.

Wir streiten nicht mehr über Meinungen („Sollten wir hohe oder niedrige Steuern haben?“). Wir streiten über Fakten, die wir nicht mehr als solche erkennen können, weil unsere psychische Abwehr sie nicht durchlässt.

Der Fall Renee Good zeigt uns, dass der amerikanische Bürgerkrieg längst begonnen hat. Er findet nicht auf den Schlachtfeldern statt, sondern in den Synapsen. Die Informationszugänge – unsere Newsfeeds – sind keine Fenster zur Welt mehr. Sie sind Spiegelkabinette, die so konstruiert sind, dass wir uns nie wieder unwohl fühlen müssen.

Solange wir den Schmerz der kognitiven Dissonanz nicht aushalten und uns stattdessen in die komfortable Lüge unserer eigenen „Bubble“ flüchten, ist Renee Good nicht tot. Sie ist Schrödingers Katze: gleichzeitig eine Terroristin und eine Heilige, je nachdem, wer hinsieht.

Und ein Land, das sich nicht einmal mehr auf den Tod einer Mutter einigen kann, ist das noch eine Nation?

Das Wahlsystem erzwingt das Schwarz-Weiß-Denken

Doch es wäre zu einfach, die Schuld allein in unseren Köpfen zu suchen. Kognitive Dissonanz ist der Treibstoff, aber der Motor ist das politische System der USA selbst. Wir müssen nicht Freud bemühen, um zu verstehen, warum Amerika brennt – ein Blick in die Verfassung reicht.

Das amerikanische Mehrheitswahlrecht („Winner-Takes-All“) ist der Brandbeschleuniger dieser Krise. Anders als in parlamentarischen Systemen, die Koalitionen und Kompromisse erzwingen, kennt das US-System nur eine brutale binäre Logik: Alles oder Nichts. Der Gewinner bekommt 100 % der Macht, der Verlierer – selbst bei 49,9 % der Stimmen – bekommt nichts.

Keine Nuance, nur Revanche

Dieses System lässt keinen Raum für Grautöne. Es gibt keine dritte Partei, die vermitteln könnte. Es gibt nur „Wir“ gegen „Die“. Wer in diesem System Differenzierung sucht, verliert.

Das führt zwangsläufig zu einer Politik der Revanche. Da der Verlierer politisch vernichtet wird, ist das oberste Ziel der Opposition nicht konstruktive Kritik, sondern die totale Blockade und die Rache bei der nächsten Wahl. Was wir im Fall Renee Good sehen, ist das Endstadium dieses Denkens: Der politische Gegner wird nicht mehr als Konkurrent betrachtet, sondern als Feind, der besiegt werden muss.

Der alte Krieg auf neuen Karten

Man braucht kein Historiker zu sein, um das Muster zu erkennen. Legen Sie eine Wahlkarte von 2024 oder 2026 über eine Karte des Bürgerkriegs von 1861. Die Linien zwischen „Blue States“ und „Red States“ zeichnen erschreckend genau die Grenzen zwischen den alten Nordstaaten (Union) und den Südstaaten (Konföderation) nach.

Der Konflikt wurde nie wirklich gelöst, er wurde nur eingefroren und in ein Zwei-Parteien-Korsett gezwängt.

- Die Demokraten beherrschen die Küsten und die urbanen Zentren (das Erbe des Nordens).

- Die Republikaner dominieren den ländlichen Raum und den Süden (das Erbe der Konföderation).

In einem solchen aufgeladenen Zweiparteienstaat, der geografisch und kulturell so tief gespalten ist, wird es sehr schwer werden, wieder aufeinander zuzugehen. Aber ich komme dann noch einmal mit der Psychologie.

Wir sitzen in der Falle. Auf der einen Seite unser Gehirn, das den Schmerz der widersprüchlichen Information nicht erträgt und sich in eine angenehme Lüge flüchtet. Auf der anderen Seite ein politisches System, das einen zwingt, sich für eine Seite zu entscheiden, und das jeden Kompromiss als Verrat bestraft.

Renee Good ist zwischen diese beiden Mühlsteine geraten. Die psychologische Dissonanz hat die Menschen blind gemacht für die Fakten. Das politische System hat die Lager so weit auseinandergetrieben, dass sie sich nicht einmal mehr hören können.

Vielleicht ist es genau jetzt an der Zeit, sich daran zu erinnern, wie zerbrechlich unsere Rationalität wirklich ist. Sigmund Freud wusste, dass die Vernunft einen schweren Stand gegen unsere tiefsten Triebe und Ängste hat. Doch er gab die Hoffnung nicht auf, dass sie langfristig überleben kann, selbst wenn sie momentan übertönt wird.

Wie er einst über die Zähigkeit der Vernunft sinnierte:

„Die Stimme des Intellekts ist leise, aber sie ruht nicht, ehe sie sich Gehör verschafft hat. Am Ende, nach unzählig oft wiederholten Abweisungen, gelingt es ihr doch.“

Blickt man heute nach Minneapolis und auf den Zustand der USA, muss man leider konstatieren: Wir befinden uns noch mitten in der Phase der Abweisungen.

(This blog has been written with the support of Mistral.AI.)

When I started my career as a professional software developer, engineer, assistant, business consultant, and architect in 1993 (many more roles I could tell, which wouldn’t help to explain what I did), I listened carefully to Neil Postman. A genius author and cultural critic, depicting our times with the right two words: INFORMATION OVERKILL.

32 years later, I think I know what he meant and partially regret that I went for the IT business. So drained by data has the well-known connotation that too much data exhausts us and psychologically distresses us. We simply get tired (and crazy) when overwhelmed by data.

But this blog is not about the psychological damages the digital world applies to us but the physical draining due to massive data computation and generation.

Of course, I am talking about the massive expansion plans in the US by big AI players to create data centers wherever they can and the bigger they can. This includes a financial investment cycle where AI companies request data centers, and big cloud suppliers that also create their own AI models offer these data centers, which need potent chip hardware vendors for enabling the implementation of the data centers that are interested and invested from their side in AI companies.

In 2025 alone, tech giants Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon are on pace to spend as much as $375 billion on data center construction and the supporting AI infrastructure. This spending, described by market analysts as an “AI arms race,” is “meeting and actually exceeding the hype”. This cycle is driven by two main forces: a domestic U.S. policy push to secure AI leadership and an international race to deploy next-generation AI models.1

Current available numbers (11/29/2025)

| Company | Investment |

| Amazon | 125 billion USD |

| Microsoft | 80 billion USD |

| Alphabet (Google) | 91-93 billion USD |

| Meta | 66-72 billion USD |

Whether this is a vicious cycle cannot yet be told, and the resemblances to the .com crisis around 2000 are applicable, but comparisons between past and present, respectively future, remain speculative.

Anyhow, this blog tries to figure out how feasible this “AI industrialization” is from a technical, financial, and ecological standpoint. Furthermore, it tries to reveal what the goals are behind an “AI industrialization” and the race for AI supremacy.

First, there is a time mismatch between the ambition to create significant AI factories within the next 18 to 36 months and the energy generation and high-voltage transmission infrastructure required to power them that takes five to ten years to permit and build.

To mitigate this gap, AI companies think they can create their own power stations close to the factory using natural gas or SMR (small modular nuclear reactors). But also that implementation takes time and requires regulation. Another idea to soften the impact on the power grid is to run the new AI factories with smart load, meaning if the power system has low demand and cheap energy is available by, e.g., renewables, the AI factories will run their intensive trainings and vice versa. Google is doing that already, using peak time of available green energy to run the training of their models.

But what drives the high demand of resources by AI compute centers?

GPUs excel at neural network calculations and training due to their parallel processing capabilities, making them highly efficient for matrix multiplication and differentiation tasks. GPUs are very focused on receiving, calculating, and transferring data, though overall less capable than CPUs. But the catch is that they require much more energy due to the high amount of data they process. And we don’t talk only about the electrical power they consume. They heat up much more than CPUs, and that requires water cooling with highly clean water.

The generative AI workloads that power this boom are exponentially more power-intensive than traditional cloud computing. This is a change in kind, not just degree.

- At the Chip Level: The NVIDIA H100 GPU, the current workhorse of AI, has a power consumption of 700 watts (W). A single GPU used at 61% utilization (a conservative estimate) consumes 3.74 megawatt-hours (MWh) per year.

- Regular CPU require (e.g., Intel Core i9-13900K, at 50% utilization): 0.55 MWh per year. This means the H100 GPU consumes about 6.7 times more energy annually than a high-end CPU under moderate workloads.

- At the Rack Level: A traditional data center rack in the early 2020s might have been designed for a 10-15 kilowatt (kW) load. Today, customers are deploying infrastructure at 100 kW per rack, and future-generation designs are being engineered for 600 kW per rack by 2027.

- At the Facility Level: A typical AI-focused hyperscale data center consumes as much electricity annually as 100,000 households. The next generation of facilities currently under construction is projected to consume 20 times that amount. 2

This power density must be understood as a baseline “IT load.” The total power drawn from the grid is even higher. For every 700W H100 GPU, additional power is required for CPUs, networking switches , and the massive energy overhead for cooling. This overhead is measured by Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE), the ratio of total facility energy to IT equipment energy. A modern facility with a PUE of 1.2, for example, must draw 120 MW from the grid to power a 100 MW IT load.

Geographic Concentration: Mapping the New Power and Water Hotspots

Data center location is not driven by proximity to population centers. It is a strategic calculation based on three primary factors:

1) the availability and cost of massive-scale power;

2) access to high-capacity fiber optic networks for low latency; and

3) access to large water supplies for cooling.

This logic has led to an extreme geographic clustering of the industry. As of late 2025, approximately one-third of all U.S. data centers are located in just three states: Virginia (663), Texas (409), and California. New key hubs are emerging rapidly in Phoenix, Arizona; Chicago, Illinois; and Columbus, Ohio.

The strain is best understood not at the state level, but at the county level, where this new gigawatt-scale load connects to the grid3.

| County | State | Operating & In Construction (MW) | Planned (MW) | Total Future Load (MW) |

| Loudoun | VA | 5,929.7 | 6,349.4 | 12,279.1 |

| Maricopa | AZ | 3,436.1 | 5,966.0 | 9,402.1 |

| Prince William | VA | 2,745.4 | 5,159.0 | 7,904.4 |

| Dallas | TX | 1,294.6 | 2,911.2 | 4,205.8 |

| Cook | IL | 1,478.1 | 2,001.8 | 3,479.9 |

| Santa Clara | CA | 1,314.7 | 552.5 | 1,867.2 |

| Franklin | OH | 1,257.4 | 483.0 | 1,740.4 |

| Mecklenburg | VA | 1,019.5 | 502.5 | 1,522.0 |

| Milam | TX | 1,442.0 | 0.0 | 1,442.0 |

| Morrow/Umatilla | OR | 2,295.5 | 101.0 | 2,396.5 |

This spending spree is part of a projected $3 trillion global investment in data centers by 2030, boosting valuations of chipmakers like Nvidia to record highs. However, the rapid, high-stakes deployment poses challenges for public planning and directly impacts consumers. Projects are often developed in secrecy—using shell companies and vague permit descriptions to avoid scrutiny—so key decisions on power and water infrastructure are made before public announcement, leaving little room for community-wide planning.

This boom is a direct cause of rising consumer bills: A 2025 ICF report projects residential electricity rates will jump 15–40% by 2030—on top of a 34% national increase from 2020 to 2025, the fastest five-year surge in recent history, with data centers as a major driver.4

The National Water Supply

The power crisis has a twin: a water crisis. The AI industry’s “thirst” is a dual-front problem, encompassing both on-site water use for cooling and a much larger, “hidden” water footprint from power generation. In the arid but high-growth regions of the American West and Southwest, this new demand is creating a dangerous, zero-sum competition for a scarce resource.

Data centers’ water use has two major impacts:

- Direct: Evaporative cooling uses 3–5 million gallons/day (like a town of 10,000–50,000 people). U.S. direct use tripled from 2014–2023.

- Indirect: Power plants (coal, gas, nuclear) consume even more water to generate electricity for data centers.

This creates a trade-off: water-efficient cooling uses more energy, and vice versa—forcing operators in water-scarce areas to choose between stressing the grid or local water supplies.

Case Study in Water Stress: The Compounding Crisis in Phoenix (Maricopa County, AZ)

Maricopa County, Arizona, is a top-three national data center hotspot, with 3.4 GW operating and another 6.0 GW planned. This boom is colliding directly with one of the most severe, long-term water crises in the nation. The region is heavily reliant on the over-allocated Colorado River and has already seen state officials limit new home construction in the Phoenix area due to a lack of provable, long-term groundwater. 5

The mitigation strategy?

Let’s focus first on the power supply crisis due to the AI boom. How do clever AI people think they can manage the problem?

AI’s 24/7 power demand outstrips intermittent renewables, pushing data centers to secure their own “firm” energy sources.

- Short-term: A natural gas boom—utilities and data centers are building new gas plants. In 2025, Babcock & Wilcox contracted 1 GW of new gas capacity for an AI data center by 2028.

- Long-term: Nuclear co-location and SMRs are now the preferred carbon-free solution. Amazon is powering a Pennsylvania data center directly from Talen Energy’s Susquehanna nuclear plant (960 MW) and partnering with Dominion Energy to deploy SMRs in Virginia, tying a $52 billion expansion to new nuclear build-outs.

Tech giants are becoming their own utilities, bypassing the grid to lock in 30–50 years of reliable, low-cost power—avoiding grid delays, price swings, and transmission bottlenecks.

How realistic is the SMR approach?

SMRs (Small Modular Reactors) are not simply scaled-up submarine reactors from the 1950s, though both share compact nuclear designs. Modern SMRs use low-enriched uranium and are optimized for civilian power, not military bursts. However, their ability to meet AI data centers’ massive, 24/7 energy demands is uncertain and delayed by major challenges:

Current Reality: Setbacks and Skepticism

- Canceled Projects: Many SMR initiatives have been halted or abandoned due to soaring costs and safety concerns. For example, NuScale—once the U.S. leader—canceled its flagship Utah project in 2023 after costs ballooned and utilities withdrew support. Other designs face similar financial and regulatory headwinds6.

- Cost Overruns: SMR electricity is currently 2.5–3 times more expensive than traditional nuclear or renewables, with first-of-a-kind plants costing $3,000–6,000 per kW (vs. $7,675–12,500/kW for large nuclear). While proponents argue costs will drop with mass production, this remains unproven at scale.

- Regulatory Hurdles: Licensing is slow and complex. Even approved designs (like NuScale’s VOYGR) struggle to attract investors or utility contracts, as risks outweigh near-term reward.

- Safety Debates: Public and expert concerns persist over new reactor designs, waste management, and proliferation risks, especially for advanced coolants (e.g., molten salt) or modular scaling.7

Potential for AI Data Centers—But Not Yet

- Theoretical Fit: SMRs could possibly provide carbon-free, always-on power (300–900 MW per plant), ideal for AI’s round-the-clock needs. Some tech giants (Amazon, Google) are betting on SMRs for post-2030 deployments, but these are long-term gambles, not immediate solutions.8

- Competing Stopgaps: Until SMRs mature, natural gas dominates new data center power projects, with nuclear’s role limited to existing plants (e.g., Amazon’s deal with Talen Energy’s Susquehanna plant) or decades-away SMRs.

- Industry Shift: Some companies now prioritize hybrid systems (solar/wind + batteries + grid upgrades) or even large conventional nuclear plants (e.g., Microsoft’s Three Mile Island revival) to avoid SMR uncertainties.9

Outlook: A Risky Bet

SMRs remain high-risk, high-reward. While they could become a backbone for AI infrastructure, their current track record—cancelled projects, cost overruns, and regulatory delays—suggests they won’t solve the near-term energy crisis for data centers. For now, gas and grid expansions are the default, with SMRs possibly emerging as a niche solution after 2030, if costs and safety issues are resolved.

How to fix the water problem?

The move to Direct-to-Chip (DLC) and immersion cooling is non-negotiable; it is the only way to cool the next generation of AI hardware. A massive positive side effect is that these “waterless” or “closed-loop” systems solve the direct water consumption problem.

Microsoft has already launched its new “zero water for cooling” data center design as of August 2024. It uses a closed-loop, chip-level liquid cooling system. Once filled at construction, the same water is continually recycled. This design saves over 125 million liters of water per year, per data center. The closed-loop system being built for OpenAI’s Michigan “Stargate” facility is similarly designed to avoid using Great Lakes water.

This technological shift is critical. It directly addresses the primary source of community opposition in water-scarce regions. However, it is not a silver bullet. By enabling more powerful and denser racks, these technologies increase the total electricity demand of the facility. In doing so, they solve the direct water footprint but may inadvertently worsen the indirect water footprint from power generation.10

Final statement

In the current situation, no one actually asks why we need this massive investment into AI. The big players will say, “Because ‘we’ need AGI” without telling us what AGI is. AGI is like the whole term intelligence, vaguely defined. So will the big players at some point tell us, “Now we have AGI,” be happy? Already now you hear even from the AI science community concern about whether AIG is feasible by current approach at all (https://techpolicy.press/most-researchers-do-not-believe-agi-is-imminent-why-do-policymakers-act-otherwise). There is a simple rule of thumb in AI. In case you increase the complexity of your model, you must also increase the complexity of your training data. But that could be the bottleneck. They have already scraped all kinds of data. I don’t talk about the quantity of data but the quality.

Meta thinks even about super intelligence. Geoffrey Hinton, who didn’t sound too optimistic in his Nobel Prize reward speech, gave a pragmatic piece of advice when thinking about super intelligence: talk about it with chickens before. They know what life is like under the control of a super intelligence.

We could do many good things with current AI without this massive planned increase of AI compute, like improving agricultural growth without using so immense chemistry.11

To rise in the clear dawn of a fatal climate crisis, such an arms race is, from my point of view, a clear sign of a suicidal species.

Citations for mobile:

- https://www.nmrk.com/insights/market-report/2025-us-data-center-market-outlook

- US data centers’ energy use amid the artificial intelligence boom …pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/10/24/what-we-know-about-energy-use-at-us-data-centers-amid-the-ai-boom

- https://www.visualcapitalist.com/map-network-powering-us-data-centers/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/technology/comments/1ny2o3n/ai_data_centers_are_skyrocketing_regular_peoples/

- https://watercenter.sas.upenn.edu/splash/water-stress-water-scarcity

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Small_modular_reactor

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1738573325005686

- https://introl.com/blog/smr-nuclear-power-ai-data-centers-2025

- https://www.commonfund.org/cf-private-equity/data-center-and-ai-power-demand-will-nuclear-be-the-answer

- https://www.multistate.us/insider/2025/10/2/data-centers-confront-local-opposition-across-america

- https://happyeconews.com/japans-ai-reforestation-drones/

Citations for Web:

- https://www.nmrk.com/insights/market-report/2025-us-data-center-market-outlook ↩︎

- US data centers’ energy use amid the artificial intelligence boom …pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/10/24/what-we-know-about-energy-use-at-us-data-centers-amid-the-ai-boom ↩︎

- https://www.visualcapitalist.com/map-network-powering-us-data-centers/ ↩︎

- https://www.reddit.com/r/technology/comments/1ny2o3n/ai_data_centers_are_skyrocketing_regular_peoples/ ↩︎

- https://watercenter.sas.upenn.edu/splash/water-stress-water-scarcity ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Small_modular_reactor ↩︎

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1738573325005686 ↩︎

- https://introl.com/blog/smr-nuclear-power-ai-data-centers-2025 ↩︎

- https://www.commonfund.org/cf-private-equity/data-center-and-ai-power-demand-will-nuclear-be-the-answer ↩︎

- https://www.multistate.us/insider/2025/10/2/data-centers-confront-local-opposition-across-america ↩︎

- https://happyeconews.com/japans-ai-reforestation-drones/ ↩︎

Kämpft nicht gegen die Entropie

Im Leben wie in der Physik scheinen wir oft gegen eine unsichtbare Kraft zu kämpfen: Entropie. Das ist die natürliche Tendenz von Systemen, in einen Zustand der Unordnung überzugehen. Ein aufgeräumter Schreibtisch wird von allein chaotisch; ein System ohne äußere Einflüsse verfällt. Jahrhunderte lang haben wir uns diesen Kampf in unserer Energiegewinnung zu eigen gemacht, indem wir die hoch geordneten chemischen Bindungen fossiler Brennstoffe durch Verbrennung gewaltsam aufbrachen, um Wärme zu erzeugen. Eine Ordnung in Form von Kohle, Öl und Gas, aufgebaut von der Natur vor ca. 360 Millionen Jahren im Zeitalter des Carbonium. Auch der Natur ist der Aufbau dieser langen, konzentrierten Kohlenwasserstoffketten nicht leichtgefallen. Sie musste ebenfalls gegen die Entropie ankämpfen und benötigte zu den heutigen (und in den letzten 250 Jahren abgebauten) Beständen ca. 60 Millionen Jahre.

Doch ist das Verbrennen von fossilen Rohstoffen der einzig wahre Weg? Sicherlich nicht.

Warum die Vergangenheit in Flammen stand?

Fossile Energieträger sind im Wesentlichen gespeicherte Sonnenenergie – in Form von Kohlenstoff- und Wasserstoffbindungen. Bei der Verbrennung reagieren diese Verbindungen mit Sauerstoff und setzen massive Mengen an Wärme frei. Warum wird so viel Wärme frei? Das liegt eben auch an der Entropie. Um ein System von einem chaotischeren (höhere Entropie) in einen geordneteren Zustand zu verwandeln, muss man Energie aufwenden. Und das hat die Natur über 60 Millionen Jahre gemacht, indem sie Arbeit verrichtet hat, abgestorbene riesige Pflanzen und Tierkadaver zu schichten, zu verpressen und wieder zu schichten, zu trocknen und zu pressen, die eben zu den hochgeordneten langen Kohlenwasserstoffketten geführt haben. Wenn „man“ das 60 Millionen Jahre macht, kommt da schon einiges an Energie zusammen. Diese in chemischer Bindung gespeicherte Energie wieder freizulassen, geht, wie wir wissen, schneller, weil die Entropie „mithilft“.

Wir haben gelernt, diese freigesetzte Energie zu nutzen. Doch dieser Prozess ist in den Skalen, in denen wir ihn durchgeführt haben, ein Kampf gegen die Natur: Er wandelt eine hochgeordnete Energieform in unkontrollierbare, diffuse Wärme um und hinterlässt dabei Abfallprodukte wie Kohlenstoffdioxid (CO₂). Auch die Folgen dieses Abfallprodukts sind trotz politischer Nebelkerzen hinlänglich und unmissverständlich bekannt.

Gibt es Alternativen?

Mit dem Fluss gehen

Die Energiewende ist kein Kampf mehr, sondern eine Akzeptanz der Naturgesetze. Anstatt gegen die Entropie zu kämpfen, nutzen wir die ständigen, natürlichen Energieströme, die uns umgeben. Ein Elektron ist das Herzstück dieser Veränderung. Es ist ein geladenes Teilchen, das auf elektrische und magnetische Felder reagiert – und genau das macht es so unglaublich gut kontrollierbar.

Die Rolle des Elektrons und der Photonen

Wir haben in den letzten 50 Jahren bewiesen, dass wir die Welt der Elektronik beherrschen. Ein Transistor, das Herzstück jedes Computers, ist ein Meisterwerk der Elektronensteuerung. Wir nutzen elektrische Felder, um Elektronen zu lenken, zu beschleunigen und zu steuern.

Gleichzeitig liefert uns die Sonne Photonen – kleine Energiepakete aus Licht. Ein Fotovoltaik-Modul nutzt diese Photonen. Wenn ein Photon auf ein Silizium-Atom trifft, wird seine Energie auf ein Elektron übertragen. Dieses freigesetzte Elektron wird in einem elektrischen Feld eingefangen und kann sofort als nutzbarer Strom in unsere Netze fließen.

Wir kämpfen nicht gegen die Natur, indem wir Bindungen aufbrechen. Stattdessen nutzen wir die natürliche Reaktion von Elektronen auf Photonen, um eine saubere und effiziente Energiequelle zu erschließen.

Eine historische Chance: Das Erbe Einsteins

Dieser Wandel ist für uns Deutsche von besonderer Bedeutung. Der wohl berühmteste (deutsche) Physiker, Albert Einstein, lieferte die entscheidende theoretische Grundlage für die heutige Solarenergie. Im Jahr 1921 erhielt er den Nobelpreis für Physik, nicht für seine Relativitätstheorie1, sondern für die Erklärung des fotoelektrischen Effekts. Er beschrieb, wie Lichtenergie (Photonen) Elektronen aus einem Material herausschlagen kann. Genau dieses fundamentale Prinzip ist die Basis jeder Solarzelle.

Wir haben die wissenschaftliche Grundlage für diese Technologie gelegt. Nun haben wir die historische Chance, das Vermächtnis Einsteins zu erfüllen und bei der Umsetzung seiner Erkenntnisse eine führende Rolle zu übernehmen.

Der Wind: Ein Fluss der Entropie

Auch der Wind ist ein perfektes Beispiel für diesen Wandel. Er ist ein direktes Resultat der Sonnenenergie, die die Atmosphäre ungleichmäßig erwärmt und dadurch Druckunterschiede erzeugt. Die Luft strömt, um diese Unterschiede auszugleichen und die Entropie des Systems zu erhöhen. Anstatt diesen natürlichen Prozess zu stören, setzen wir Windturbinen ein, die sich in diesen Windstrom einfügen. Sie nutzen die kinetische Energie, die im System vorhanden ist, um Strom zu erzeugen. Es ist ein elegantes Beispiel dafür, wie wir die natürlichen Gesetze nutzen, anstatt gegen sie zu arbeiten.

Der Reality-Check: Manche fordern zu Recht einen Reality-Check der Energiewende. Sie warnen, dass der Weg holprig ist. Sie haben recht. Es ist naiv zu glauben, dass das reine Wissen um Photonen und Elektronen ausreicht. Die wahre Herausforderung liegt in der “praktischen Entropie”: dem bürokratischen Widerstand, den komplexen Gesetzen und den physikalischen Grenzen unserer Netze. Und natürlich von unserer Fähigkeit, hoch organisierten, monopolistischen Konzernen (niedrige Entropie) die Angst zu nehmen, in den Zustand höherer Entropie in Form von chaotisch-demokratisch-prosumerorientierten Bürgerenergie-Systemen (hohe Entropie) überzugehen. Da staunt auch die Entropie, was für Widerstände man ihr da in den Weg legt.

Dennoch ist auch dies kein Kampf gegen die Natur, sondern ein Umgang mit den realen Gegebenheiten. Ein Netzwerk aus Stromleitungen ist ein geordnetes System, das ständig von Störungen und Schwankungen bedroht wird – eine Form von Entropie, die wir beherrschen müssen. Speichersysteme wie Batterien sind der Versuch, die zeitliche Unordnung der Sonnen- und Windenergie zu glätten. Hinzu kommen Smart Grids, die über einen intelligenten Lastenausgleich und modernste Sensoren eine permanente Regulierung im Netz ermöglichen. Sie helfen, die Energie genau dorthin zu leiten, wo sie gebraucht wird, indem sie Verbraucher und Erzeuger intelligent miteinander vernetzen.

Der Reality-Check ist kein Argument, um aufzugeben. Er ist eine Aufforderung, pragmatisch und hart an den realen Problemen zu arbeiten, die uns davon abhalten, das volle Potenzial der Natur zu nutzen.

Ein neues Verständnis von Energie

Die Energiewende ist also keine technologische Revolution, sondern ein konzeptioneller Wandel. Wir haben verstanden, dass wir nicht gegen die Entropie kämpfen müssen, indem wir geordnete Systeme zerstören. Stattdessen können wir mit dem Fluss gehen und die Energie des Universums nutzen, die uns in Form von Sonnenlicht und Wind zur Verfügung steht. Der wahre Fortschritt liegt nicht im Kampf, sondern in der Akzeptanz der Naturgesetze.

- Die Relativitätstheorie war viel bedeutender, aber die Nobeljuroren hatten wohl Angst, seine Theorie wäre “Hoax” würde man heute sagen. War sie aber nicht, sie ist die bis heute am besten experimentell bestätigte Theorie der Physik. ↩︎

Bandits or The Social Dilemma

This blog was arranged with the assistance of using Le Chat from Mistral.AI.

Bandits: A Clever Approach to Decision Making in Machine Learning…with some inevitable side effects

Imagine you’re in a casino, standing in front of a row of slot machines (often called “one-armed bandits”). Each machine has a different probability of paying out, but you don’t know which one is the best. Your goal is to maximize your winnings, but how do you decide which machine to play?

You might start by trying each machine a few times to get an idea of which ones are more likely to pay out (this is called exploration). Once you have some data, you might focus more on the machines that seem to give the best rewards (this is called exploitation). The challenge is balancing between exploring enough to find the best machine and exploiting the best machine you’ve found so far to maximize your winnings (so simply the basic conceptual ideas of capitalism).

This scenario is a classic illustration of the multi-armed bandit problem, a fundamental concept in machine learning that deals with making sequential decisions under uncertainty.

What Are Bandits?

The term “bandit” comes from the analogy of slot machines, which are sometimes colloquially referred to as “one-armed bandits” because they can take all your money if you’re not careful. In machine learning, the multi-armed bandit problem is a framework for addressing the exploration-exploitation trade-off.

Key Concepts in Bandit Problems

- Arms:

- These are the different choices or actions you can take. In the slot machine analogy, each arm corresponds to a different slot machine. In a real-world scenario, arms could represent different ads to display, different content recommendations, or different treatments in a clinical trial.

- Rewards:

- When you choose an arm (take an action), you receive a reward. For example, if an ad is clicked, you receive a reward (e.g., revenue from the click). If a recommended video is watched for a long time, that could be considered a high reward.

- Exploration vs. Exploitation:

- Exploration: Trying out different arms to gather more information about their expected rewards.

- Exploitation: Choosing the arm that has given the highest average reward so far to maximize immediate payoff.

- The core challenge is finding the right balance between exploration and exploitation.

- Regret:

- A measure of how much better you could have done if you always chose the best arm (with the highest expected reward) from the start. The goal is to minimize regret over time (until you regret you ever played with the bandits).

Why Are Bandits Important in Machine Learning?

Bandit problems are a special case of reinforcement learning where the goal is to learn from interactions with an environment to make decisions that maximize cumulative reward. They are particularly useful in scenarios where you need to make decisions sequentially and learn from feedback to improve future decisions.

Applications of Bandit Algorithms

- Online Advertising:

- Selecting which ad to show to a user to maximize click-through rates. The bandit algorithm explores different ads and exploits the ones that perform best.

- Content Recommendation:

- Recommending articles, videos, or products to users based on their past interactions. The goal is to maximize engagement by balancing between showing popular items and exploring new ones.

- Clinical Trials:

- Assigning patients to different treatments to find the most effective one while minimizing the number of patients receiving suboptimal treatments.

- A/B Testing:

- Efficiently testing different versions of a webpage or app feature to determine which one performs best without requiring extensive testing periods.

- Resource Allocation:

- Deciding how to allocate limited resources (e.g., servers, network bandwidth) to different tasks to maximize overall efficiency.

Types of Bandit Algorithms

There are several strategies to solve bandit problems, each with its own approach to balancing exploration and exploitation:

- Epsilon-Greedy:

- Choosing an arm in the epsilon-greedy method is like deciding whether to stick with a familiar restaurant or try a new one. With a probability of 1−ϵ (exploitation), you go to the restaurant you know you like (the arm with the highest average reward). With a probability of ϵ (exploration), you choose a new, random restaurant to try (a random arm), even though you don’t know if it’s good.

- This method is simple because it’s easy to understand the core idea: sometimes you go with what you know works, and other times you take a chance to find something even better. However, it’s not always the most efficient strategy. For example, if you find an excellent new restaurant, this method will still sometimes force you to try other random restaurants, even if they’re not as promising.

- Thompson Sampling:

- The Thompson Sampling method is like being a detective with a hunch. Instead of just picking the arm with the highest average reward, you have a belief about how good each arm could be. This belief is represented as a range of possibilities, not just a single number.

- At each step, you “imagine” the best-case scenario for each arm by randomly picking a value from its range of possibilities. Then, you choose the arm that has the best imagined value. If an arm hasn’t been tried much, its range of possibilities is broad, so it has a good chance of being picked to be explored. If an arm has been tried many times and consistently gives good rewards, its range of possibilities is narrow and high, making it a strong candidate for exploitation.

- This way, the algorithm naturally focuses on exploring arms that are more uncertain but have the potential for high rewards while also exploiting arms that have a proven track record. It’s a more intuitive and efficient way to balance exploration and exploitation than just choosing randomly.

- Upper Confidence Bound (UCB):

- Think of the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) method as being a cautiously optimistic gambler. Instead of just looking at an arm’s average reward (how much it’s paid out so far), you also consider how uncertain you are about its true value.

- You calculate an “optimism score” for each arm. This score is a combination of its average reward and a bonus for how little you’ve tried it. The bonus is bigger for arms you haven’t played much because you’re still very uncertain about their potential.

- At each step, you simply choose the arm with the highest optimism score. This means you’ll either pick the arm that has the best track record (exploitation) or a less-played arm that has a high potential to be better (exploration). The algorithm naturally favors exploring arms that have high uncertainty, as they represent the biggest “unknown unknowns” that could lead to a massive payoff.

- Contextual Bandits:

- Imagine you’re recommending an article to a user. Instead of just picking the one that’s been most popular in the past, you also consider who the user is (their age, interests, what they’ve read before) and what the article is about (its topic, author, length).

- This is the core idea of contextual bandits. It’s like having a more informed gambling machine. You’re not just pulling a lever blindly; you’re using extra clues to make a smarter decision. For each user, you use their specific information (the context) to predict which arm (article) is most likely to give a high reward (a click or a read).

Example: Choosing Between Ads

Let’s consider a practical example of using bandits in online advertising:

- Arms: Different ads that can be shown to users.

- Rewards: Whether a user clicks on the ad (click-through rate).

- Exploration: Show different ads to gather data on their effectiveness.

- Exploitation: Show the best-performing ad more frequently to maximize clicks.

Using a bandit algorithm like Thompson Sampling, the system can dynamically adjust which ads to show based on observed click-through rates, balancing the need to explore new ads and exploit the best-performing ones.

Implementing Bandits

Here’s a simple example of how to implement an epsilon-greedy bandit algorithm in Python:

import numpy as np

class Bandit:

def __init__(self, num_arms, epsilon=0.1):

self.num_arms = num_arms

self.epsilon = epsilon # Number of times each arm was pulled self.counts = np.zeros(num_arms) # Estimated value of each arm self.values = np.zeros(num_arms)

def select_arm(self):

if np.random.rand() < self.epsilon:

# Explore: choose a random arm

return np.random.randint(self.num_arms)

else:

# Exploit: choose the arm with the highest estimated value

return np.argmax(self.values)

def update(self, chosen_arm, reward):

# Update the count and estimated value for the chosen arm

self.counts[chosen_arm] += 1

n = self.counts[chosen_arm]

value = self.values[chosen_arm]

# Update the estimated value using incremental averaging

self.values[chosen_arm] = value + (reward - value) / n

# Example usage

num_arms = 3

bandit = Bandit(num_arms)

# Simulate pulling arms and receiving rewards

for _ in range(1000):

chosen_arm = bandit.select_arm()

# Simulate reward: let's assume arm 0 has a higher mean reward

reward = np.random.normal(0.5 if chosen_arm == 0 else 0, 1)

bandit.update(chosen_arm, reward)

print("Estimated values for each arm:", bandit.values)

print("Number of pulls for each arm:", bandit.counts)In this example, the bandit algorithm learns that arm 0 has a higher expected reward and exploits this knowledge to maximize cumulative rewards over time.

Conclusion

Bandit problems provide a powerful framework for decision-making under uncertainty. By balancing exploration and exploitation, bandit algorithms can efficiently learn which actions yield the best rewards without requiring extensive prior knowledge. This makes them particularly useful in real-world applications like online advertising, content recommendation, and resource allocation.

Understanding and implementing bandit algorithms can help you make smarter decisions in dynamic environments, optimizing for long-term rewards rather than short-term gains. Whether you’re a data scientist, machine learning engineer, or simply curious about decision-making algorithms, bandits offer an intuitive and effective approach to sequential decision-making.

Bandits in Social Media: The Double-Edged Sword

In our previous section, we introduced the concept of bandit algorithms as a clever approach to decision-making under uncertainty. We saw how these algorithms can efficiently balance exploration and exploitation to optimize outcomes in various applications, from online advertising to clinical trials.

But what happens when these powerful algorithms are applied to social media platforms? On one hand, bandit algorithms can enhance user experience by personalizing content and recommendations. On the other hand, they can also lead to unintended and harmful consequences, as vividly depicted in the documentary “The Social Dilemma.”

The Power of Bandits in Social Media

Social media platforms are a perfect application for bandit algorithms. Here’s how they are typically used:

- Content Personalization:

- Social media platforms use bandit algorithms to decide which posts, videos, or articles to show in a user’s feed. The goal is to maximize user engagement, measured by likes, shares, comments, and time spent on the platform.

- Each piece of content is an “arm,” and the algorithm learns which types of content generate the most engagement for each user.

- Advertisement Optimization:

- Similarly, bandit algorithms help determine which advertisements to display to which users to maximize click-through rates and conversions.

- This allows platforms to optimize ad revenue while also providing users with ads that are relevant to their interests.

- Notification Strategies:

- Platforms use bandit algorithms to decide when and how to send notifications to users to maximize engagement without causing too much annoyance.

- Different notification strategies (timing, content, frequency) are the arms, and the reward is user engagement following the notification.

The Dark Side: Bandits and the Social Dilemma

While bandit algorithms can improve user experience and engagement, their use in social media also raises significant ethical concerns. These concerns are at the heart of “The Social Dilemma,” a documentary that explores the unintended consequences of social media algorithms on society (unintended but widely accepted consequences).

1. Addiction and Mental Health

Bandits and Addiction:

- Bandit algorithms are designed to maximize engagement, often by showing users content that evokes strong emotional reactions. This can lead to addictive behaviors as users become conditioned to seek out these emotional triggers.

- The constant stream of engaging content can contribute to anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues, particularly among adolescents and young adults.

Example:

- A bandit algorithm might learn that a particular user engages more with videos that evoke strong emotional responses, such as outrage or excitement. The algorithm will then prioritize showing similar content to keep the user engaged, potentially leading to addiction and negative mental health outcomes.

2. Echo Chambers and Polarization

Bandits and Echo Chambers:

- Personalization algorithms, including bandits, tend to show users content that aligns with their existing beliefs and preferences. This creates echo chambers where users are exposed only to information that reinforces their existing views.

- Over time, this can lead to increased societal polarization, as people become less exposed to diverse viewpoints and more entrenched in their own beliefs.

Example:

- If a user frequently engages with content that supports a particular political viewpoint, the bandit algorithm will prioritize showing similar content. This can reinforce the user’s beliefs and contribute to a polarized society where people with different viewpoints struggle to understand each other.

3. Spread of Misinformation

Bandits and Misinformation:

- Content that is sensational or controversial often generates more engagement, as it elicits strong emotional reactions. Bandit algorithms, which aim to maximize engagement, may inadvertently prioritize such content.

- This can lead to the rapid spread of misinformation and fake news, as these types of content often generate high levels of engagement.

Example:

- During elections, misinformation and sensationalist content can spread rapidly due to the engagement-driven nature of bandit algorithms. This can undermine democratic processes by misleading voters and amplifying divisive content.

4. Exploitation of Vulnerable Populations

Bandits and Vulnerability:

- Bandit algorithms may exploit vulnerabilities in certain populations. For example, adolescents and individuals with mental health issues may be more susceptible to addictive content and misinformation.

- By maximizing engagement without considering the potential harm, these algorithms can exacerbate issues like anxiety, depression, and self-harm behaviors.

Example:

- If a vulnerable user frequently engages with content related to self-harm or eating disorders, the bandit algorithm may continue to show similar content, potentially exacerbating the user’s condition.

5. Privacy Concerns

Bandits and Privacy:

- Effective personalization and recommendation systems rely on extensive data collection about users’ behaviors, preferences, and personal information.

- This raises significant privacy concerns, as users may not be fully aware of the extent of data collection or the ways in which their data is being used.

Example:

- Social media platforms collect vast amounts of data on user interactions, which are used to train bandit algorithms. This data can include sensitive information about users’ personal lives, preferences, and vulnerabilities.

Addressing the Ethical Concerns

Given the significant ethical concerns surrounding the use of bandit algorithms in social media, it is crucial to explore potential solutions and mitigations:

1. Ethical AI Design

Principle: Incorporate ethical considerations into the design and implementation of AI systems from the outset.

Actions:

- Develop algorithms that prioritize user well-being and societal good alongside engagement metrics.

- Implement safeguards to prevent the spread of harmful or misleading content.

- Use fairness-aware algorithms to ensure that recommendations do not disproportionately favor certain groups or viewpoints.

2. Transparency and Accountability

Principle: Ensure that AI systems are transparent and accountable to users and society at large.

Actions:

- Provide clear and accessible explanations of how algorithms work and how they influence the content users see.

- Allow users to see and adjust the data that is being collected about them.

- Establish independent oversight bodies to audit and regulate AI systems.

3. User Empowerment

Principle: Empower users to make informed choices about their social media use and the content they consume.

Actions:

- Provide tools and settings that allow users to customize their feeds and limit exposure to certain types of content.

- Offer educational resources to help users understand the potential impacts of social media on their mental health and well-being.

- Implement features that encourage healthy usage patterns, such as screen time limits and reminders.

4. Regulatory Oversight

Principle: Establish robust regulatory frameworks to govern the use of AI and data collection in social media.

Actions:

- Implement data protection laws that give users control over their personal information and how it is used.

- Enforce transparency requirements for AI systems used in social media platforms.

- Create regulations that limit the use of exploitative or manipulative algorithms.

5. Public Awareness and Advocacy

Principle: Raise public awareness about the ethical implications of AI-driven social media and advocate for responsible practices.

Actions:

- Support research and public discourse on the societal impacts of AI and social media.

- Advocate for policies and practices that prioritize user well-being and societal good.

- Encourage ethical practices within the tech industry through advocacy and public pressure.

Conclusion: Balancing Innovation and Responsibility

Bandit algorithms are a powerful tool for decision-making under uncertainty, and their application in social media platforms has revolutionized how content and advertisements are personalized and delivered. However, as depicted in “The Social Dilemma,” these algorithms also pose significant ethical and societal challenges.

By understanding the potential harms and implementing strategies to mitigate them, we can harness the benefits of bandit algorithms while minimizing their negative impacts. It is crucial for technology developers, policymakers, and society at large to work together to ensure that AI-driven systems are designed and used in ways that prioritize user well-being, societal good, and ethical considerations.

As we continue to innovate and develop more sophisticated algorithms, we must also remain vigilant about their broader impacts on society. By doing so, we can create a future where technology enhances our lives without compromising our well-being and democratic values.

That was of course, a summary created by a balanced AI. I don’t see that the politicians, but also society at large really want to work on the many negative side effects of the bandit exploration and exploitation system. That’s terrible.

Bandits explained by YouTube

YouTube’s recommendation system is one of the most advanced and largest-scale industrial recommender systems existing, serving billions of users and processing hundreds of billions of data points daily. At the core of its functionality is a sophisticated interplay between deep neural networks and bandit algorithms, which together enable personalized video

recommendations that maximize user engagement. The following text provides a comprehensive technical and ethical analysis of YouTube’s bandit system and recommendation engine, focusing on how these components integrate to present new videos to users, the challenges they address, and the implications of their design.

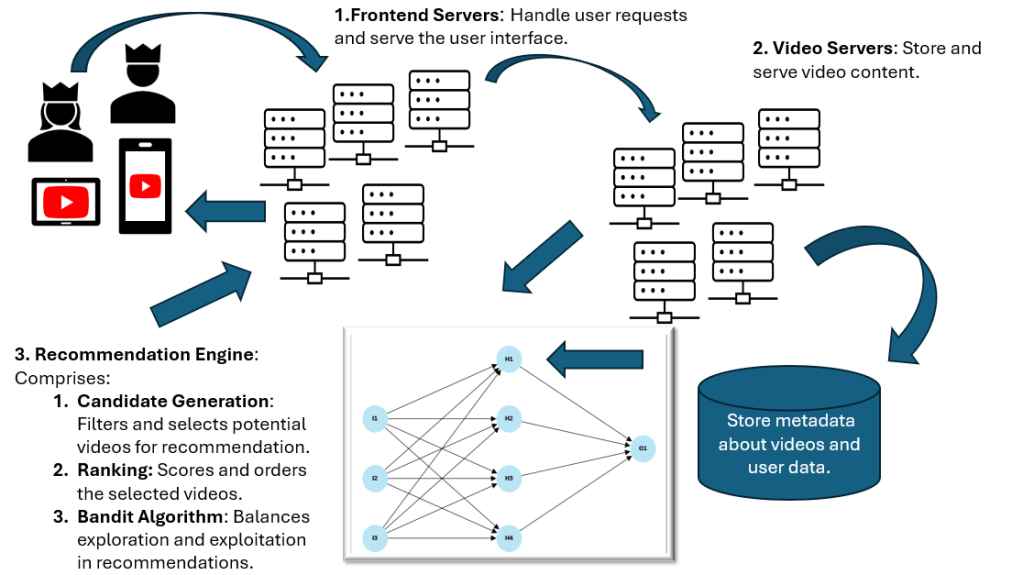

High-Level Architecture of YouTube’s Recommendation System

YouTube’s recommendation engine is structured as a multi-stage pipeline designed to

efficiently narrow down millions of videos to a personalized set of recommendations for each

user. The architecture consists primarily of two deep neural networks: one for candidate

generation and another for ranking.

Candidate Generation Network: This network processes user activity history and

contextual features to retrieve a subset of hundreds of videos from YouTube’s vast

corpus of over 800 million videos. The goal is to efficiently filter out irrelevant content

and focus on videos that are likely to be of interest to the user. This stage leverages

collaborative filtering and embeddings learned from user behavior and video metadata

to capture complex relationships and similarities between users and videos. (1 2 3 4).

Ranking Network: The ranking network takes the candidate videos and assigns each a

score based on a rich set of features, including video metadata, user engagement

history, and contextual signals. This network predicts metrics such as expected watch

time and user satisfaction to prioritize the most relevant and engaging videos. The final

recommendations are then filtered for content quality, diversity, and appropriateness

before being presented to the user 1 2 3 4

Bandit Systems in YouTube’s Recommendation Engine

Bandit algorithms are fundamental to YouTube’s ability to balance exploration and exploitation in its recommendations. Originating from the multi-armed bandit problem, these algorithms enable the system to make decisions under uncertainty by continuously learning from user feedback.

Role of Bandits: YouTube uses bandit algorithms to decide when to show new or less

popular videos (exploration) versus videos known to maximize engagement

(exploitation). This balance is critical to maintaining user satisfaction and engagement

over time, as it prevents the system from getting stuck in a local optimum of only

recommending popular content 5 6 7.

Types of Bandits: The ε-greedy algorithm is a classic example used in YouTube’s

system, where with probability ε, the system explores a new video, and with probability

1-ε, it exploits the best-known video. Other variants, such as Upper Confidence Bound

(UCB) and Thompson Sampling, may also be employed to optimize the trade-off

between exploration and exploitation in different contexts 5 8.

Contextual Bandits: YouTube’s system integrates contextual information—such as user

features (e.g., demographics, past behavior) and video features (e.g., metadata,

embeddings)—into the bandit framework. This allows the algorithm to make more

informed decisions tailored to the specific user and video context, improving

recommendation relevance and engagement 5 9.

Integration with Neural Networks: The bandit algorithms work in concert with the neural

networks in the candidate generation and ranking stages. The neural networks provide

the contextual embeddings and predictions that inform the bandit’s decision-making,

enabling a dynamic and adaptive recommendation strategy 7 2.

This integration allows YouTube to continuously refine its recommendations based on realtime user feedback, ensuring that the system remains responsive to changing user

preferences and content trends 7.

Neural Networks in YouTube’s Recommendation Engine

Neural networks are the backbone of YouTube’s ability to process vast amounts of data and

extract meaningful patterns for personalized recommendations.

Neural Network Models: YouTube employs deep neural networks (DNNs), recurrent

neural networks (RNNs), and transformers to model user behavior and video features.

These models are capable of learning high-dimensional embeddings that capture

complex relationships between users and videos, enabling accurate predictions of user

preferences 1 2.

Training and Inference: The neural networks are trained on hundreds of billions of

examples using distributed training techniques. This massive scale allows the models to

generalize well across diverse user behaviors and video characteristics. During

inference, the models assign scores to videos based on user features and contextual

information, enabling real-time personalized recommendations.1 2

Personalization: Neural networks incorporate user history, preferences, and

engagement metrics to tailor recommendations. They learn embeddings that represent

user interests and video attributes, facilitating the matching of users to relevant content.

This personalization is crucial for maintaining user engagement and satisfaction 1 2.

Handling Fresh Content and Cold Start: The system uses natural language processing

(NLP) and word embeddings to address the cold-start problem for new videos with

limited behavioral data. By analyzing textual metadata, YouTube can infer content

similarity and recommend new videos to interested users without relying solely on past

user interactions.4

The neural networks’ ability to process and learn from vast datasets enables YouTube to

continuously improve its recommendations, adapting to user feedback and evolving content trends.2

Technical Design and Implementation

YouTube’s recommendation system is engineered to scale and operate in real-time, handling billions of users and videos with high efficiency.

Scalability: The system uses distributed training and serving infrastructure to manage

the computational complexity and data volume. This allows YouTube to train models with

approximately one billion parameters on hundreds of billions of examples and serve

recommendations with low latency.1 2

Real-Time Processing: Efficient algorithms and data structures enable real-time

candidate generation and ranking. The system processes user interactions and

contextual information on the fly, ensuring that recommendations are responsive and

relevant to the current user session 1236

Feedback Loops: User feedback—such as watch time, likes, dislikes, and survey

responses—is continuously incorporated into the system. This feedback refines the

models and bandit algorithms, enabling the system to adapt to changing user

preferences and improve recommendation quality over time.1 10

Quality Assurance: YouTube implements diversity and novelty metrics to ensure a

balanced mix of popular and niche content. The system also filters out inappropriate or

low-quality content to maintain user satisfaction and platform integrity.2 11

This technical design supports YouTube’s goal of delivering engaging, personalized, and high-quality recommendations at scale while remaining responsive to user behavior and content.

Finally, a diagram

That was a lot of text, and I suppose many will not make it until here, but I come from the last millennium when it was more common to write texts without many diagrams, but I know that was some time ago.

I don’t know whether you can understand it by this diagram, but anyhow it’s a little difficult to capture this complex system in one sketch.

But what I knew was that there was probably something that could do it much better than me: I asked PowerPoint’s CoPilot to make nice slides about the YouTube architecture. I passed to CoPilot some prompts from Mistral.AI, and within 20 seconds I got 20 professional-looking slides with excellent content about all that is mentioned in this blog focused on the YouTube system.

That reminds me, for a crucial part of my job description, it is, besides programming, to make such nice presentations about complex technical systems. But to compete with something that can do it in 20 seconds might be difficult. So I wait for my universal income that the guys from Silicon Valley promised, and I trust them…not really.

Final (human) conclusion

I am a member of the beginning generations, born in 1966, who were used to full airtime on television. Though not exactly in my childhood and beginning youngster time, television stopped at midnight with the national anthem and started somewhere at lunch sending in between a test picture. But apart from that I could watch a lot of TV from my childhood on. The major difference to the concept above was no one really knew what you had watched. If you wanted to watch critical and even cynical things about society, you watched at a late time. But if you had watched something at all, no one knew except the people in your household.

You had to talk about it, and that we did of course. We had very meaningful discussions, e.g. about why JR Ewing had again shaken things up in Dallas, and enjoyed many discussions around that. Hopefully some elder people at least will remember that time without looking it up on Google. It was a totally different time, and after writing this blog I really ask myself whether this time was ever true.

But it was foreseeable that this time would change. At the end of the seventies, video recorders and computer games gave the users a first chance to personalize their viewing experience.

Regarding YouTube, I really liked my personalized videos. I have seen their incredible content (the word content in this context no one would have understood in the eighties or earlier). But the problem is obvious: we are creating sophisticated, personalized bubbles and losing more and more contact with each other day by day.

Will there be meaningful regulation by authorities on a local, state, regional, or global level? I don’t think so.

But you personally can do it and find out how beautiful this world is without social media. Of course it is much more difficult for young people than for me who was raised in a totally different age. But I tell you it’s worth a try at least reducing the airtime on social media.

- Deep Neural Networks for YouTube Recommendations

- “Cracking the Code: Unveiling the Magic Behind YouTube’s Recommendation Algorithm” | by Sneh Shah | Medium

- Deep neural networks for YouTube recommendations | PPT

- How YouTube’s Recommendation System Works – Particular Audience

- Bandits for Recommender Systems

- What are bandit algorithms and how are they used in recommendations?

- The YouTube Algorithm: How It Works in 2025 | by Amit Yadav | Medium

- Vinija’s Notes • Recommendation Systems • Multi-Armed Bandits