With this blog, I want to compress the AR6 Longer Report with its major findings from 85 to 13 pages. Whereas the summary is mainly achieved by using ChatGPT’s (3.5) summarize functionality, I also added some interpretation of the content by myself. To enable the reader to differentiate what is my personal interpretation and what is the outcome of ChatGPT’s summing up features, there is the following rule: ChatGPT’s summarizing is written in italic style, whereas personal comments are written in regular style.

Personal introduction to observation of anthropogenic climate change:

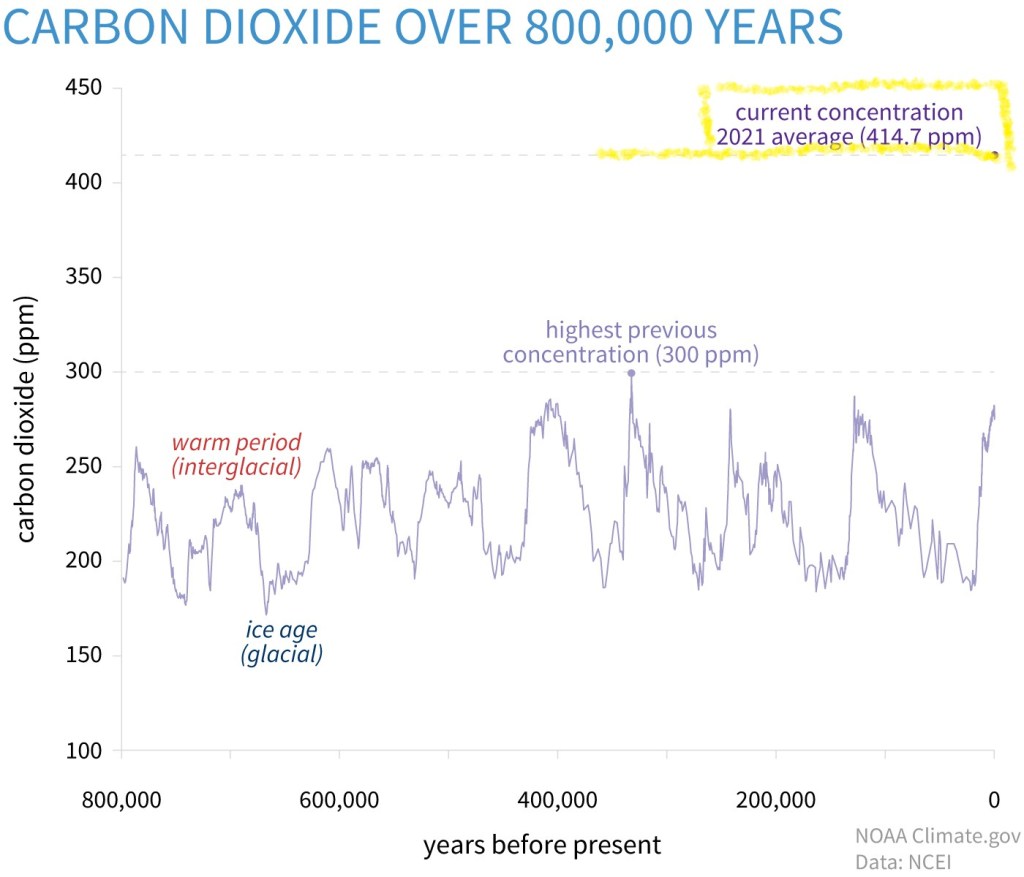

I start with a graphic taken from the climate dashboard created by NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which is US America’s environmental intelligence agency: https://www.climate.gov/climatedashboard

The first image shows the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere over the last 800,000 years (Homo sapiens are supposed to exist on earth for about 300,000 years).

As you can easily see from the diagram above, the CO2 atmospheric concentration has been changing periodically, but today’s value of about 415ppm is far over the average of the last 800,000 years. Whereas the periodic changes in CO2 concentration are driven by the Milankovitch cycles relating ice and warm ages to variations of Earth’s rotation axis (Earth’s rotation moves along a cone, phenomena called precession (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milankovitch_cycles)), the current concentration is according to the vast majority of scientists human induced by our industrial revolution running for 250 years. You might ask how you will be able to measure the CO2 concentration 800,000 years ago if Homo sapiens exist only for 300,000 years? You can get this information by digging deep into the ice of Antarctica. The deeper you drill, the older the ice is and inside the ice old air bubbles are encapsulated, carrying still the set-up of the ancient air thousands of years ago.

So why does this observed concentration change in CO2 concern scientists so much?

It is this plot that makes the trouble:

What do you see on the diagram above? 20,000 years ago, that was the time of the last ice age on this planet. Then, over a period between six and seven thousand years, the average global temperature rose by 6 degrees. Definitely, this temperature increase was not driven by humans. But then 10 thousand years ago, the global average temperature was quite stable. This time period is called Holocene. And it’s not by accident that in this phase, human man kind developed to 8 billion inhabitants. A stable climate was at least a very good pre-condition for such a population growth.

What concerns the scientists now is that little spike on the right-hand sight of the time axis.

In the last 250 years, the global average temperature has increased by 1.1 degrees. This growth rate is much higher than that of 18 thousand years ago. At that time the avarage, global temperature was rising by one dergree per thousand years. That means the current global temperature change we face is by a factor four faster than during the end of the last ice age. The temperature change, although it is for a human, still quite slow, is from a climate change viewpoint very fast. You can see that more clearly if you focus on global average temperature change for the last eight thousand years:

Projections by computer simulations of the temperature evolution in case of ongoing rising CO2 concentration with same rate as today in the atmosphere, forecast in the second half of this century another rising of average temperature by 3–5 degrees, which would be catastrophic.

But this is my short summary of the situation we are in. I am not a climate expert, but I was an engineer. I worked 5 years in the area of LASER technology, including the use of CO2 gas LASERS. So, I still have at least a basic understanding of how electromagnetic radiation interacts with matter.

But let’s see how the experts of IPCC see the current and future situation regarding anthropogenic climate change. But I warn you ahead, you must be brave to reach the end of this summary.

The original IPCC AR6 Report you find here:

And now the squeezed report generated by AI:

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), provides a summary of the current state of knowledge of climate change, its impacts, and mitigation and adaptation measures. The report is based on the latest scientific, technical, and socio-economic literature since the publication of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) in 2014. The report reflects the increasing diversity of those involved in climate action and integrates the main findings of the AR6 Working Group reports and the three AR6 Special Reports. The report recognizes the interdependence of climate, ecosystems, biodiversity, and human societies and the close linkages between climate change adaptation, mitigation, ecosystem health, human well-being, and sustainable development. The report is structured into three sections:

- Current Status and Trends,

- Long-Term Climate and Development Futures,

- Near-Term Responses in a Changing Climate.

The key findings are formulated as statements of fact or associated with an assessed level of confidence using the IPCC calibrated language. The report uses multiple analytical frameworks, including those from the physical and social sciences, to identify opportunities for transformative action that are effective, feasible, just, and equitable.

In the chapter “Current Status and Trends“, the report discusses the observed warming of the Earth’s surface and its causes. It notes that the global surface temperature has increased by approximately 1.1 °C above the 1850-1900 baseline in the period from 2011 to 2020, with larger increases over land than over the ocean. It attributes this observed warming to human activities, primarily due to the increase in greenhouse gases (GHGs) such as CO2 and CH4 (methane), partly offset by aerosol cooling. In this chapter the report also states that the global surface temperature has increased faster since 1970 than in any other 50-year period over at least the last 2000 years. The range of human-caused global surface temperature increase from 1850-1900 to 2010-2019 is estimated to be between 0.8 °C to 1.3 °C, with the best estimate of 1.07 °C. It is likely that well-mixed GHGs contributed a warming of 1.0 °C to 2.0 °C, and other human drivers, primarily aerosols, contributed a cooling of 0.0 °C to 0.8 °C. The natural drivers changed global surface temperature by ±0.1 °C, and internal variability changed it by ±0.2 °C.

The report also highlights that GHG concentrations have increased since around 1750 due to human activities, with atmospheric concentrations of CO2, CH4, and N2O reaching unprecedented levels in at least 800,000 years. It notes that the concentrations of CH4 and N2O (laughing gas) have increased far more than the natural multi-millennial changes between glacial and interglacial periods over at least the past 800,000 years (please refer as well to first graphic in this blog) . The net cooling effect from anthropogenic aerosols peaked in the late 20th century.

(personal remark: The success in the late 70ties and 80ties to filter out carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide during industrial processes unfortunately increased global warming even further.)

The report continues, stating that human influence has caused widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere, and biosphere, which are unprecedented over many centuries to many thousands of years. Human influence is also noted as the main driver of the warming of the atmosphere, ocean, and land, as well as the retreat of glaciers, decrease in Arctic sea ice area, and the acidification of the surface open ocean. Additionally, it notes that human-caused climate change is affecting many weather and climate extremes across the globe, including heatwaves, heavy precipitation, droughts, and tropical cyclones. It is very likely that hot extremes have become more frequent and intense, while cold extremes have become less frequent and severe, with high confidence that human-caused climate change is the main driver of these changes.

The IPCC AR6 report states that accelerating implementation of adaptation responses is important to bring benefits to human well-being and vulnerable populations, and that delayed mitigation action will increase global warming and decrease the effectiveness of adaptation options. Comprehensive responses integrating adaptation and mitigation can harness synergies and reduce trade-offs, and mitigation actions can improve air quality and human health. Delayed adaptation and mitigation actions risk cost escalation, lock-in of infrastructure, stranded assets, and reduced feasibility and effectiveness of adaptation and mitigation options. Societal choices and actions implemented in this decade will determine the extent to which medium- and long-term development pathways will deliver higher or lower climate resilient development outcomes. Enabling conditions would need to be strengthened to realise opportunities for deep and rapid adaptation and mitigation actions and climate resilient development, and barriers to feasibility would need to be reduced or removed to deploy mitigation and adaptation options at scale.

The report stresses the importance of an inclusive, equitable approach to integrating adaptation, mitigation, and development, which can harness synergies for sustainable development and reduce trade-offs. Shifting development pathways towards sustainability and advancing climate resilient development is enabled when governments, civil society, and the private sector make development choices that prioritize risk reduction, equity and justice, and when decision-making processes, finance, and actions are integrated across governance levels, sectors, and timeframes. The report also underscores that accelerated financial support for developing countries is critical to enhance mitigation and adaptation action.

Heatwaves have become more frequent and intense across most land regions since the 1950s, while cold extremes, including cold waves, have become less frequent and severe due to human-caused climate change. Marine heatwaves have doubled in frequency since the 1980s, and human influence has likely contributed to most of them since at least 2006. Additionally, heavy precipitation events have increased in frequency and intensity since the 1950s over most land areas, and human-caused climate change is likely the main driver. Furthermore, agricultural and ecological droughts have increased in some regions due to increased land evapotranspiration, and it is likely that the global proportion of major tropical cyclone occurrence has increased over the last four decades.

The report also discusses various climate change mitigation pathways and their potential impacts on sustainable development, indicating that pathways that assume using resources more efficiently or shift global development towards sustainability have the most pronounced synergies with respect to sustainable development. The report notes that strengthening climate change mitigation action entails more rapid transitions and higher up-front investments but brings benefits from avoiding damages from climate change and reduced adaptation costs. The report acknowledges that cost-benefit analysis remains limited in its ability to represent all damages from climate change, including non-monetary damages, or to capture the heterogeneous nature of damages and the risk of catastrophic damages. Nonetheless, the report finds that the global benefits of limiting warming to 2°C exceed the cost of mitigation, and that limiting global warming to 1.5°C instead of 2°C would increase the costs of mitigation but also increase the benefits in terms of reduced impacts and related risks and reduced adaptation needs.

The report highlights the negative impacts of climate change on food and water security due to changing precipitation patterns, warming, and loss of cryospheric elements. While agricultural productivity has increased globally, climate change has slowed this growth and negatively impacted crop yields in mid and low latitude regions, with some positive impacts in high latitude regions. Ocean warming has contributed to a decrease in maximum catch potential, compounded by overfishing for some fish stocks. Climate change has also adversely affected food production from shellfish aquaculture and fisheries. Additionally, climate change has caused adverse impacts on human and mental health, and increased displacement and involuntary migration due to extreme weather and climate events. Vulnerability to climate hazards is higher in economically and socially marginalized communities, especially among Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Overall, climate change has caused widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people, with the most vulnerable people and systems disproportionately affected.

The IPCC AR6 report has also found that the policies and laws addressing mitigation have expanded since the previous report. Climate governance has also helped in providing frameworks for policy development and implementation, and many regulatory and economic instruments have been deployed successfully. The costs of low-emission technologies such as solar, wind, and lithium-ion batteries have decreased consistently, and many low or zero-GHG intensity production processes are at the pilot stage. However, emissions have increased globally since 2010, and more needs to be done to achieve deep reductions in GHG emissions. Furthermore, the coverage of policies across sectors is uneven, and policies remain limited for emissions from agriculture and from industrial materials and feedstocks. The report also highlights the importance of international financial cooperation as a critical enabler of low-GHG and just transitions.

The report positively states that there has been progress in adaptation planning and implementation across all sectors and regions. Adaptation options are available that can enable, accelerate, and sustain adaptation implementation, and growing public and political awareness has resulted in many countries and cities including adaptation in their climate policies and planning processes. Adaptation actions to water-related risks and impacts make up the majority of all documented adaptation, and various adaptations are being implemented in different sectors, including agriculture, land management, biodiversity and ecosystem services, and urban adaptation. Adaptation can generate multiple additional benefits and can reduce climate risks. Globally tracked adaptation finance has shown an upward trend, but represents only a small portion of total climate finance and is unevenly distributed across regions and sectors. Integrated, multi-sectoral solutions that address social inequities, differentiate responses based on climate risk and cut across systems, can increase the feasibility and effectiveness of adaptation in multiple sectors.

The IPCC AR6 report points out several barriers to effective climate action, including challenges related to implementing mitigation strategies, lack of resources for adaptation, and insufficient financing for both mitigation and adaptation efforts. The report also notes that many countries, cities, and companies have committed to achieving net-zero emissions, but policies to deliver on these pledges are limited. In addition, the report acknowledges that current development pathways may create barriers to accelerated mitigation, and that structural factors such as economic and natural endowments, political systems, cultural factors, and gender considerations affect climate governance. Finally, the report identifies maladaptation as a significant risk and stresses the need for long-term planning and flexible, multi-sectoral approaches to adaptation in order to avoid adverse outcomes.

Furthermore report indicates that future global warming will depend on greenhouse gas emissions, with a range of possible warming from 1.4°C to 4.4°C by 2081-2100 depending on the emissions scenario. To limit warming to 1.5°C or less than 2°C, deep and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are necessary, including reductions in other pollutants like methane. Failure to achieve these reductions will result in further irreversible changes to the climate system such as ocean acidification, deoxygenation, and sea level rise. With every additional increment of global warming, changes in extremes will become larger, with hot and cold temperature extremes, heavy precipitation and flooding events, and more frequent and severe agricultural and ecological droughts projected to increase in all regions. Deep, rapid, and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions will lead to improvements in air quality within a few years, reductions in trends of global surface temperature discernible after around 20 years, and over longer time periods for many other climate impact-drivers.

(personal remark: please note the report regards deoxygenation as potential thread by 2081-2100, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deoxygenation)

The report emphases that the global climate-related risks have increased significantly in recent years due to human activities such as burning of fossil fuels and deforestation. The risks are projected to become increasingly severe with every increment of global warming, and the long-term impacts will be up to multiple times higher than currently observed. Depending on the level of global warming, the assessed long-term impacts will be high to very high for all Reasons for Concern (RFCs). The report projects that global warming of 1.5°C will result in an increase in climate-related risks to health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, human security, and economic growth, and the risks will increase sharply in the mid- and long-term with further global warming. The report also highlights that the risks from climate change will become increasingly complex and more difficult to manage with every increment of warming. Finally, the report states that Solar Radiation Modification (SRM) approaches, if implemented, would introduce a widespread range of new risks to people and ecosystems and that a lack of robust and formal SRM governance poses risks as deployment by a limited number of states could create international tensions.

==personal remark: Solar Radiation Modification (SRM) is a proposed geoengineering technology that aims to reflect a portion of the sun’s incoming radiation back into space to reduce the amount of solar energy absorbed by the Earth’s atmosphere and surface, thereby reducing global warming. This could be achieved through a variety of methods, including injecting reflective aerosols into the stratosphere or brightening marine clouds by adding salt particles.==============================================================

The report summarizes the likelihood and risks of abrupt and irreversible changes due to global warming. It states that higher warming levels increase the likelihood and impacts of abrupt and irreversible changes, leading to the extinction of species, loss of biodiversity, and other ecological imbalances. The risks associated with tipping points or singular events, such as ice sheet instability or ecosystem loss from tropical forests, transition to high or very high risks at certain warming levels. Sea level rise is inevitable for centuries to millennia due to continuing deep ocean warming and ice sheet melt, and the risks associated with coastal ecosystems, people, and infrastructure will continue to increase beyond 2100. The text also mentions low-likelihood, high-impact outcomes that could occur at regional scales due to global warming, such as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation weakening, which could cause abrupt shifts in regional weather patterns and water cycles. The probability and rate of ice mass loss increase with higher global surface temperatures. The text emphasizes the importance of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to limit these risks and irreversible changes.

The effectiveness of adaptation to reduce climate risk is documented for specific contexts, sectors, and regions, but its effectiveness decreases with increasing warming. Common adaptation responses in agriculture and water-related adaptation options will become less effective from 2°C to higher levels of warming. With increasing global warming, more limits to adaptation will be reached, and losses and damages will increase, particularly among the poorest and most vulnerable populations. Integrated, cross-cutting multi-sectoral solutions increase the effectiveness of adaptation. Maladaptive responses to climate change can create lock-ins of vulnerability, exposure, and risks that are difficult and expensive to change and exacerbate existing inequalities. Sea level rise poses a distinctive and severe adaptation challenge, and responses to ongoing sea level rise and land subsidence include protection, accommodation, advance and planned relocation, and ecosystem-based solutions.

The report states that in order to limit global temperature increase to a certain level, there is a finite carbon budget that cannot be exceeded. The remaining carbon budget (RCB) for limiting warming to 1.5°C with a 50% likelihood is estimated to be 500 GtCO2, and for 2°C with a 67% likelihood is 1150 GtCO2. If the annual CO2 emissions between 2020-2030 stayed at the same level as 2019, the resulting cumulative emissions would almost exhaust the remaining carbon budget for 1.5°C and exhaust more than a third of the remaining carbon budget for 2°C. The historical cumulative net CO2 emissions between 1850 and 2019 amount to about four-fifths of the total carbon budget for a 50% probability of limiting global warming to 1.5°C and to about two-thirds of the total carbon budget for a 67% probability to limit global warming to 2°C. In scenarios with increasing CO2 emissions, the land and ocean carbon sinks are projected to be less effective at slowing the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere, and additional ecosystem responses to warming not yet fully included in climate models would further increase concentrations of these gases in the atmosphere.

Personal Note, that means in very short: If we continue like now, the 1.5 degree limitation will be gone 2030, and one third of budget would have been already exhausted to keep the 2 degree limitation.

Limiting human-caused global warming to a specific level requires limiting cumulative CO2 emissions and reaching net-zero or net-negative CO2 emissions, along with strong reductions of other GHG emissions. Modelled pathways show that reaching net-zero GHG emissions results in a gradual decline in surface temperature, and carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is necessary to achieve net-negative CO2 emissions. The timing of net-zero CO2 emissions, followed by net-zero GHG emissions, depends on several variables, including the desired climate outcome, the mitigation strategy, and the gases covered. Global net-zero CO2 emissions are reached in the early 2050s in pathways that limit warming to 1.5°C and around the early 2070s in pathways that limit warming to 2°C. Non-CO2 GHG emissions are strongly reduced in all pathways, but residual emissions of CH4 and N2O and F-gases remain at the time of net-zero GHG.

The IPCC report states that limiting global warming to a specific level requires reducing cumulative CO2 emissions and achieving net zero or net negative CO2 emissions, along with strong reductions in other greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Global pathways to achieve this involve rapid and deep reductions in emissions across all sectors, including industry, transport, buildings, and urban areas. CDR (carbon dioxide removal) methods such as afforestation, reforestation, improved forest management, agroforestry, and soil carbon sequestration are necessary to achieve net-negative CO2 emissions. However, there are challenges to implementing CDR, such as cost, governance requirements, and potential impacts and risks. Overshooting a warming level can have adverse impacts on human and natural systems, including irreversible impacts on ecosystems. The larger the overshoot, the more net negative CO2 emissions are needed to return to a given warming level.

The IPCC AR6 SYR report highlights that mitigation and adaptation options can have both synergies and trade-offs with other aspects of sustainable development, which depend on the pace and magnitude of changes and the development context, including inequalities. The report emphasizes that transitions to low-emission systems in the energy sector can have multiple co-benefits, including improvements in air quality and health, and that many land management and demand-side response options in agriculture, land, and food systems can contribute to eradicating poverty and eliminating hunger while promoting good health and wellbeing, clean water and sanitation, and life on land. However, some adaptation options that promote intensification of production may have negative effects on sustainability.

Additionally, the report highlights that observed adverse impacts and related losses and damages, projected risks, trends in vulnerability, and adaptation limits demonstrate that transformation for sustainability and climate resilient development action is more urgent than previously assessed. Climate resilient development integrates adaptation and GHG mitigation to advance sustainable development for all. However, climate resilient development pathways have been constrained by past development, emissions, and climate change and are progressively constrained by every increment of warming, particularly beyond 1.5°C. The report notes that climate resilient development will not be possible in some regions and sub-regions if global warming exceeds 2°C and that safeguarding biodiversity and ecosystems is fundamental to climate resilient development but has limited capacity to adapt to increasing global warming levels, making climate resilient development progressively harder to achieve beyond 1.5°C warming.

The IPCC AR6 report states that the magnitude and rate of climate change and associated risks depend strongly on near-term mitigation and adaptation actions. Global warming is likely to reach 1.5°C between 2021 and 2040, and is very likely to exceed 1.5°C under higher emissions scenarios. Many adaptation options have medium or high feasibility up to 1.5°C, but hard limits to adaptation have already been reached in some ecosystems, and the effectiveness of adaptation to reduce climate risk will decrease with increasing warming. Societal choices and actions implemented in this decade determine the extent to which medium- and long-term pathways will deliver higher or lower climate resilient development. Without urgent, effective, and equitable adaptation and mitigation actions, climate change increasingly threatens the health and livelihoods of people around the globe, ecosystem health, and biodiversity, with severe adverse consequences for current and future generations.

Global modelled pathways that limit warming to 1.5°C with no or limited overshoot and in those that limit warming to 2°C assuming immediate actions involve rapid and deep GHG emissions reductions. Without these actions, global GHG emissions will continue to increase, and losses and damages will continue to disproportionately affect the most vulnerable populations. All global modelled pathways that limit warming to 2°C or lower by 2100 involve GHG emission reductions in all sectors, and the contributions of different sectors vary across modelled mitigation pathways.

The report states that global warming will continue to increase in the near term, and every region in the world is projected to face further increases in climate hazards, leading to increased risks to ecosystems and humans. Natural variability will modulate human-caused changes, either attenuating or amplifying projected changes, especially at regional scales, with little effect on centennial global warming. Risks for humans and ecosystems depend more strongly on changes in vulnerability and exposure than on differences in climate hazards between emissions scenarios. Principal hazards and associated risks expected in the near-term are increasing intensity and frequency of hot extremes, increasing frequency of marine heatwaves, near-term risks for biodiversity loss, more intense and frequent extreme rainfall, high risks from dryland water scarcity, continued sea level rise and increased frequency and magnitude of extreme sea level events encroaching on coastal human settlements and damaging coastal infrastructure, and an increase in ill health and premature deaths. Multiple climate change risks will increasingly compound and cascade in the near term, and with every increment of global warming, losses and damages will increase, becoming increasingly difficult to avoid and being strongly concentrated among the poorest vulnerable populations.

The report emphasizes the importance of prioritizing equity, social justice, inclusivity, and rights-based approaches in adaptation and mitigation actions, which can lead to more sustainable outcomes and reduce trade-offs. Redistributive policies across sectors and regions that shield the poor and vulnerable and social safety nets can enable deeper societal ambitions and resolve trade-offs with sustainable development goals. The report also highlights the importance of meaningful participation and inclusive planning, informed by cultural values, Indigenous Knowledge, local knowledge, and scientific knowledge, to help address adaptation gaps and avoid maladaptation. Additionally, the report emphasizes the need for broad and meaningful participation of all relevant actors in decision-making at all scales to enable deeper societal ambitions for accelerated mitigation and climate action more broadly, and build social trust, support transformative changes and an equitable sharing of benefits and burdens. The report also acknowledges the different starting points and contexts of countries and regions, and enabling conditions for shifting development pathways towards increased sustainability will differ, giving rise to different needs. The report also highlights various economic and regulatory instruments that have been effective in reducing emissions and practical experience that informed instrument design to improve them while addressing distributional goals and social acceptance. Finally, the report emphasizes the importance of eradicating extreme poverty, energy poverty, and providing decent living standards to all in these regions in the context of achieving sustainable development objectives in the near-term, which can be achieved without significant global emissions growth.

The IPCC AR6 SYR report discusses various options to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change in different sectors. In the energy sector, it highlights the need for major transitions to net-zero CO2 energy systems, including a reduction in fossil fuel use, use of Carbon Capture and Storage, electrification, alternative energy carriers, energy conservation, and integration across the energy system. The report also mentions that many response options are technically viable and supported by the public. In industry, reducing emissions will require coordinated action throughout value chains, including demand management, energy and materials efficiency, circular material flows, abatement technologies, and transformational changes in production processes. In cities, integrated planning that incorporates physical, natural, and social infrastructure is critical for achieving deep emissions reductions and advancing climate resilient development. Urban greening and combining green/natural and grey/physical infrastructure adaptation responses can mitigate climate change and reduce risk from extreme events. The report also discusses responses to ongoing sea level rise and land subsidence in low-lying coastal cities and settlements and small islands.

The report highlights the substantial potential for mitigation and adaptation in agriculture, forestry, and land use, as well as the oceans. Conservation, improved management, and restoration of forests and other ecosystems offer the largest share of economic mitigation potential. Maintaining the resilience of biodiversity and ecosystem services at a global scale depends on effective and equitable conservation of approximately 30–50% of Earth’s land, freshwater and ocean areas. Effective adaptation options exist to help protect human health and wellbeing. Enhancing knowledge on risks and available adaptation options promotes societal responses, and behaviour and lifestyle changes supported by policies, infrastructure and technology can help reduce global GHG emissions. Finally, the report emphasizes the importance of cooperative, international efforts to enhance institutional adaptive capacity and sustainable development to reduce future risks of involuntary migration and displacement due to climate change.

The IPCC AR6 report states that there are more synergies than trade-offs between mitigation and adaptation actions and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, the existence of trade-offs and synergies depends on the context and scale of implementation, and can be avoided or compensated for with additional policies, investments, and financial partnerships. Many mitigation and adaptation actions have multiple co-benefits with SDGs, particularly in the areas of energy, urban and land systems, and ecosystem management. When implementing mitigation and adaptation together, multiple co-benefits and synergies for human well-being, ecosystem, and planetary health can be realized. Effective governance is needed to limit trade-offs of some mitigation options and ensure the involvement of all stakeholders.

Improved availability and access to finance can accelerate climate action, both for mitigation and adaptation. Climate resilient development requires international cooperation, inclusive governance, and coordinated policies, especially for vulnerable regions and sectors. Both adaptation and mitigation finance need to increase many-fold, and public finance can leverage private finance to address real and perceived regulatory, cost and market barriers. Although there is sufficient global capital and liquidity to close global investment gaps, there are barriers to redirect capital to climate action, especially in developing countries facing economic vulnerabilities and indebtedness. Scaling up financial flows requires clear signalling from governments and the international community. The challenge of closing gaps is largest in developing countries, and up-front risks deter economically sound low carbon projects. A robust labelling of bonds and transparency is needed to attract savers. Average annual modelled mitigation investment requirements for 2020 to 2030 in scenarios that limit warming to 2°C or 1.5°C are a factor of three to six greater than current levels, and total mitigation investments (public, private, domestic and international) would need to increase across all sectors and regions.

In summary, the IPCC AR6 report highlights the importance of international cooperation and coordination to achieve ambitious climate goals and climate-resilient development. The largest climate finance gaps and opportunities are in developing countries, and increased support from developed countries and multilateral institutions is critical to enhance mitigation and adaptation action. Technology innovation, adoption, diffusion, and transfer, accompanied by capacity building, knowledge sharing, and technical and financial support can accelerate the global diffusion of mitigation technologies, practices, and policies. The report also emphasizes the importance of multi-sectoral solutions that cut across systems to increase the feasibility, effectiveness, and benefits of mitigation and adaptation actions. When combined with broader sustainable development objectives, such measures can yield greater benefits for human wellbeing, social equity and justice, and ecosystem and planetary health.

End of the message. If you really managed to come to this point of the text without missing some passages of the text, you are brave and you have at least a certain anticipation in which dramatic situation we are.